Interview with Paolo D’Angelo

Issue 1 – Author: Giacomo Bruni

Paolo D’Angelo is a professor of Aesthetics at the University of Roma Tre. A graduate of the University of Roma Uno, “La Sapienza”, he received his PhD (Dottorato) from the University of Bologna. He was also the Head of the Department of Philosophy, Communication, Media and Performing Arts of Roma Tre University from January 2013 to December 2018.

He was formerly a professor at Messina University (1999-2000). He has taught Aesthetics at Roma Tre since September 2004.

Chief areas of interest: Aesthetics of the visual arts; environmental Aesthetics; analytic Aesthetics; History of Aesthetics; German philosophy; contemporary Italian philosophy.

G.B.

The world in which we live in is a globalized one. The exchange of information is instantaneous, people and goods move freely and with ease. Such technological advances have led us to the illusion that reading one Wikipedia page is enough to possess any type of knowledge – we are then left with pieces of information that do not have any cultural substrate.

This rings especially true when we think about how non-western cultures are discussed – they often get read in a westernized key or, even worse, as just inferior.

We do not seem to believe that other cultures have created systems of thoughts different and equally as complex as the western one, such as the Chinese one for instance.

The basis of all thought systems in China is a holistic point of view that finds its main expression in the concepts of balance and harmony. This fundamental idea is also at the root of the environmental aesthetics that from Yijing reach Confucian and Daoist thoughts.

So, keeping all of this in mind, let me ask you: how can we solve the problems that afflict our times, including those related to the environment? Could adopting somewhat of a holistic point of view aid us?

P.D.

First of all, I am not an expert in oriental cultures, what little I know comes mostly from the attendance of western studies on the matter and from the interest in the landscape, because renowned oriental cultures – in particular the Chinese and Japanese ones – have a long tradition in landscape art.

In your question two things are mentioned that are quite different in my opinion, one is what is currently called infosphere – which is the presence of a huge amount of information accessible online – and then the other is globalization, which are two obviously connected aspects; however, they are not the same, in the sense that the first concerns the transmission of information and the second concerns economic and social interactions. The question “In what sense within these two phenomena can there be a greater exchange between east and west?” precisely qualifies the difference between the two orders of phenomena, in the sense that undoubtedly the presence of such a vast amount of information online could make an exchange between east and west easier. Likewise, it is equally possible that there will be an increase in exchanges caused by the interaction between a greater number of people and relationships.

However, I would separate the cognitive theme proper to the sphere of information and the one that is much more complex and full of difficulties which is represented by the phenomenon that currently goes under the term globalization.

You ask if in the Eastern culture there are elements closer to the Environmental Aesthetics than those practiced or discussed in the Western culture. If you had asked the reverse, the answer would be yes, since it is clear that in the Eastern texts you quoted there is a greater openness towards nature than that that is usually found in western texts.

My perplexity derives from a matter of principle: I have the impression that the comparison between ideologies should be kept separate, that is, on one hand the Eastern philosophies and on the other the Western philosophies and practices (which are the habits, customs etc.), because it seems to me that one of the biggest problems is that if on the theoretical level a difference can be found that is not always found in the practice, in fact there are western philosophers who show this openness towards nature (Hans Jonas or Rosario Assunto, for example).

On a practical level we have to disagree about the fact that the way of life, the organization of society, types of production of consumption, and therefore the repercussions on nature of both the Western and Eastern society are different, indeed they are often extraordinarily similar. I mean, despite the presence of an accentuated sensitivity for nature in Chinese thought, Chinese society is as polluting as and perhaps more than western societies, and similar things can be said about Japan.

Certainly there is a fundamental difference in the attitude towards nature from the theoretical point of view, in the sense that if we look at modern philosophy (the discourse is different for ancient philosophy, because there are authors who could be considered not far from a symbiotic relationship with nature, such as Pythagoras) we see an increase in an instrumental and ‘extraneous’ conception of nature. The consideration of nature as an object, as an instrument, as a field to be enslaved, exploited, is accentuated starting from Bacon, but after all, a large part of modern science that stems from modern philosophy tends to see nature in a very different way from how it is seen in the east. This is inevitable.

However, as I was saying before, the product of modern philosophy – from Descartes to Bacon – is in large part modern science, and modern science is in this moment western as well as eastern, and we must be careful in keeping separate the plans of what happens in society and what can be obtained from the thought of the authors.

G.B.

Environmental Aesthetics has put art aside a little, since the aesthetic experience of nature wants to be lived, of course, in nature; but unfortunately, for a series of different reasons, not everyone can have this experience. This also applies to the environmental problem, which despite being a planetary issue, is rarely felt strongly by people, even more so if an environmental crisis is happening far away from them.

In your opinion, in this contemporary world, can art assume an important role and put man and nature in contact?

P.D.

On the issue of the relationship between art and the environment, and the possibility that environmental art will help to raise awareness of environmental problems, I would say that environmental art in the West has probably evolved over time precisely in this sense. It started from a very manipulative attitude, very artificial, also very violent towards nature – I am thinking of American Land Art – and it has now gotten to moments of interaction with nature that are lighter, more respectful, more suitable for the contexts in which the art is practiced. Sensitivity has certainly increased, (for example less polluting materials are used). This sensitivity led to act in nature in a non-invasive way, and to simply record the encounter with the environment. The first names that should be mentioned are those of Richard Long and Hamish Fulton. I would say that one of the last phenomena is the presence of an art that wants to act as a denunciation of environmental problems; one representative of this art is England-based artist Olafur Eliasson. He has taken specific actions to raise awareness on climate change and melting ice caps.

This type of sensitivity is certainly present, what must be avoided is a too close relation between environmental reporting and artistic production, not in the sense that it cannot be done, but we must be careful that not just the message, but also the action has some characteristic that brings you closer to the substance. It must not just be a gesture of denunciation, otherwise there is the risk of closing art in the bottlenecks of propaganda, which can be propaganda for very good purposes, but still propaganda remains.

In your studies on the landscape we see how, starting from Simmel’s thought, man and nature are two separate elements. Indeed the landscape arises precisely when this division becomes more marked, so much so that Environmental Aesthetics has put aside the term ‘landscape’.

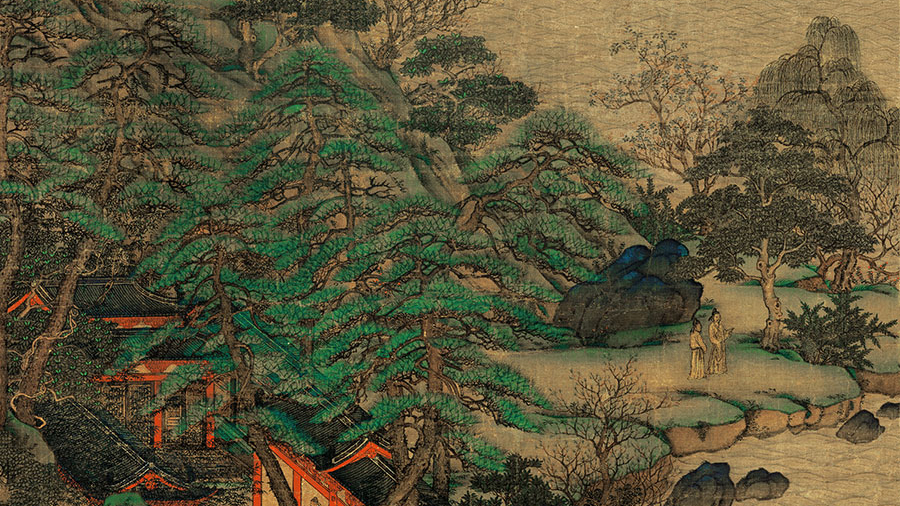

Instead in China, what in the west we commonly call Chinese landscape painting continues to be one of the main artistic expressions, but in this pictorial form nature is not represented as seen by the subject, but rather the painter will try to represent nature in its essence, because he does not take a position of superiority over it, nor does he have any interest in representing his materialistic point of view, thus erasing the subject.

Could the almost total disappearance of landscape painting in the western artistic world be linked to this phenomenon?

The separation from nature within the landscape is unfortunately a very true factor. The concept of landscape as it was inaugurated in the West assumes a separation from nature, we always see the landscape in the western tradition moving from a condition of estrangement from nature, there is no perception of immersion in nature or the contiguity between man and nature. The concept of landscape was born on the basis of an original separation.

I’ll give a very clear example. There is a poem by Schiller entitled The Walk, which describes the encounter with the landscape starting from the exit from the city. So first of all you must have been taken away, and only then, going out into nature, finding it again, you can perceive the landscape. The premise of all this is that the link has been broken, if there had been no break the notion of landscape as it is in the West would not have formed. This applies to many western landscape theorists.

Basically landscape painting itself is a typical portrayal of the environment of the city. In other words, it begins to spread when and where there is a city life.

The first autonomous landscape painters are painters who work in the city, in Holland or in the Flemish countries. Our tradition of the landscape starts from a condition of separation from nature. This can be observed in many approaches towards the landscape. For example Cézanne – referring to the painting of the mountain Sainte-Victoire in the south of France – says that he sees the landscape, but that the farmers who live at the foot of the mountain and who work the land on the slopes of the mountain do not see the landscape, because they are too much a part of the landscape. This is very characteristic of the western vision of the landscape, a vision that starts from the nostalgia of nature, this nostalgia arises from a separation and a distance that the subject tries to overcome. It is true that there may also be other traditions in the West closer to a man/nature relationship that does not presuppose this separation, but they are basically minor traditions.

Our vision of the landscape is, again, a very nostalgic one, it is based on an original separation from nature. The same belief that the real landscape is born from nothing more than the reflection of an artistic creation – that is, landscape painting – confirms this way of looking at it. At the base of the landscape there is an artificial operation. From this point of view oriental cultures and oriental landscape painting, in particular Chinese landscape painting, could probably teach us about a different kind of relationship with nature. I repeat I know very little about these cultures, but this very strong element of separation in the theory of western landscape is probably not present in eastern cultures.

Western painting in recent decades has hardly kept pace with other forms of artistic expressions. Could a change of approach towards the world, such as embracing the holistic conception of the existence in a Chinese fashion, give us new food for thought and open new avenues for creativity?

There is no doubt that traditional landscape painting loses a lot of ground in art as it progresses today. After all, the nineteenth century was the last century of landscape painting, in the twentieth century there are artists who paint landscapes (Rosai or Morandi for instance) but there is no real contemporary tradition of landscape painting.

So much so that when the artists wanted to recreate a relationship with nature, they did not go through landscape painting, but towards forms of intervention in nature, forms of environmental art, forms of Land Art etc.

There is no doubt that the purely pictorial tradition of the landscape is in jeopardy. The road that can be traveled today in the West from this point on is represented by the new media. For example, video recordings allow a representation of nature that does not have the characteristics of objectivity, of artificiality that are typical of static landscape painting; therefore it is possible to recover landscape experiences in the form of life within the landscape as it relates with nature.

There are artists, for example the group (a duo in fact) Flatform, which work between Milan and Berlin and produce landscape videos in which one tries to get out of the purely visual dimension, so the landscape is recovered in its auditory dimensions, in lighting, especially in its variable dimensions; it is not presented as a static, but as a moving landscape. This type of approach can allow the creation of a relationship with nature, which in traditional landscape painting seems difficult to rediscover.

Read the article from the magazine, download it from here