Wenren hua 文人画 and the Benjaminian flâneur: a question of perspectives

By; Aurora Vivenzio

In the essay Perspective as symbolic form (1927), Erwin Panofsky stated that: «Perspective is the mirror of how the world is perceived». If we consider the spatial and temporal ideas as concepts that have always guided pictorial and artistic productions, these abstractions find their mode of representation and concretization through the perspective medium, a precious and dear concept to the Western world, but not as decisive and binding in pictorial productions of Mountain and Water painting (Shanshui hua 山水画).

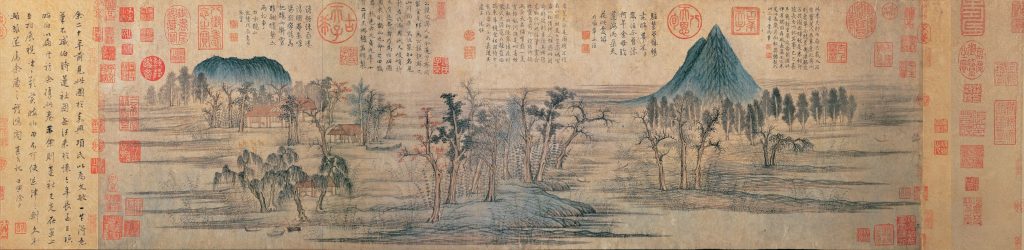

In Roman and Pompeian paintings, we observe that space is conceived as finite and inhomogeneous, therefore rendered in a determined time, while the Renaissance masters considered it as infinite and homogeneous, therefore in an indefinite time. In China, starting from the Tang Dynasty, space and time are depicted as units in continuous evolution, where time never stops determining itself and returns to its infinite nature and where space is limited and then extends beyond the composition.

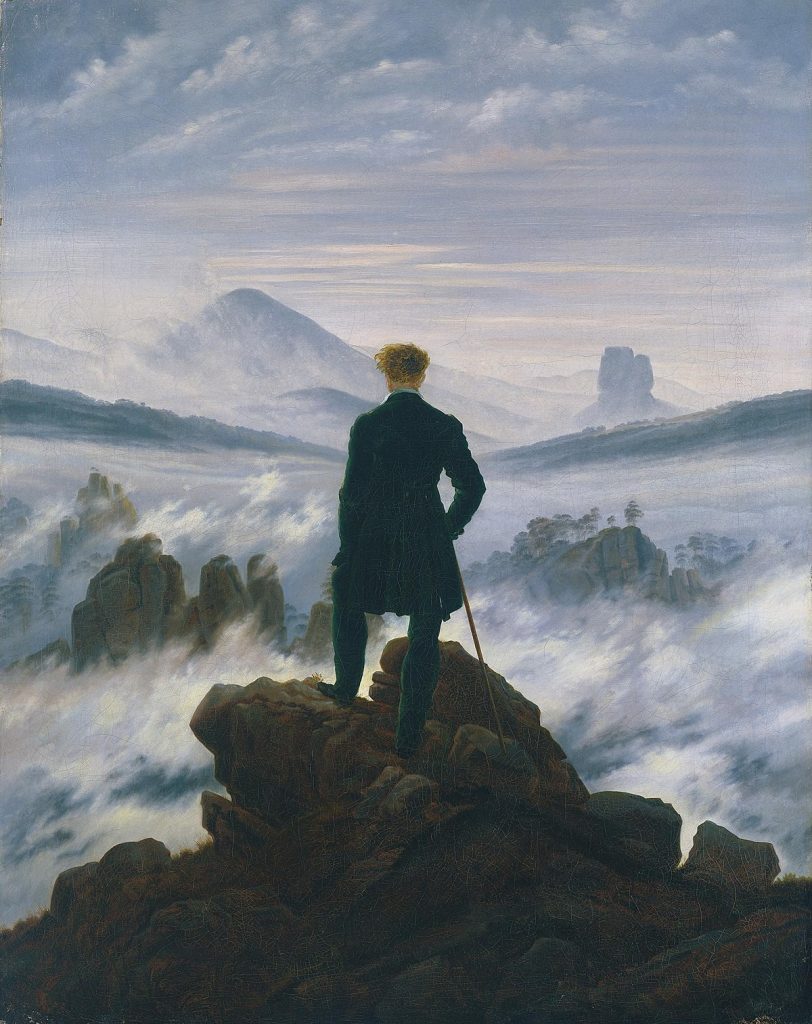

In landscape paintings, or any other Western subject, perspective translates as a sign of an anthropocentric vision of the world, where it is considered the subject as the center of the work and where the landscape becomes a pretext for contextualizing the scene. It is precisely on this basis that a great difference with the Chinese pictorial conception arises. The subject in the works of Chinese artists becomes a pretext to capture the attention of the beholder, to captivate him and to draw him into the picture, making him perceive a natura naturans, in its making and undoing (fig.1,2)

This appropriation and restitution of the phenomenal world is not an operation that occurs only as an aesthetic act, but as an existential act, a testimony of the artist’s presence, a hic et nunc.

For this reason, we could read the figure of Wenren hua 文人画 as the contemporary, modern artist, the Benjaminian flâneur who regains possession of his relationship with environment, with nature and with the world around him through artistic practice. We can, therefore, see these two very similar figures in terms of the action and conceptual practice they perform, that is, both are an active part of the vision (active shows) and they express it on scroll – or on other supports – what they have reworked, reinterpreted and “generated within them” of the world they live in. Furthermore, both express themselves with a plurality of languages ranging from the pictorial and iconological ones to the calligraphic art, which become operational methods for “abstracting” reality and reconfiguring it through new meanings.

Both the flâneur figure and Wenren hua are based on a Yinyi 隐逸 lifestyle, hidden and far from the mundanity and glory, which allows them to be free, to manage their time and to be able to concentrate on their artistic practice. They are the privileged of society and therefore it has precisely been this condition of isolation that has allowed them to develop that awareness of their role, of their relationship with life, with nature, with the world and consequently also with themselves. This hiding through the passages for the flâneur and through the mountains and the forests for the Chinese literatus, to observe, to concentrate, to reflect, can be read as an act of opening to and towards the world and of reappropriation of their relationship with real life. This is the only possible way that allows them to penetrate and understand things, making them their own, without distorting or governing them, but simply transposing and translating them through the eye of the mind and the spirit.

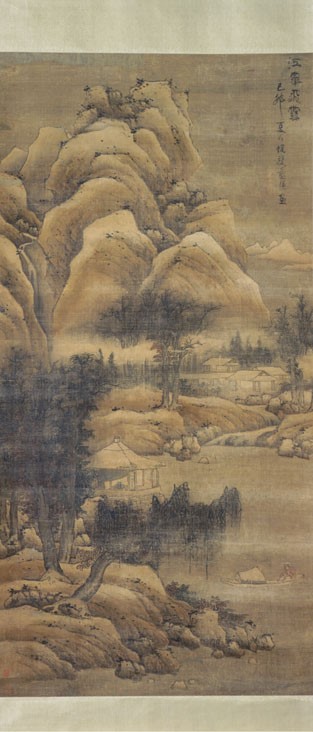

The act of active observation of spaces translates into the composition of the Chinese scroll using multiple perspectives, which at the same time expresses the continuous becoming, flowing of the matter.

Linguistically perspectiva is a word, derived from Latin, that indicates “to see through”. Similarly, in the Chinese culture, we see through the subjective spirit of the painter where everything “appears” 透 and it is secretly revealed to us.

Even the sign takes on a completely different value from that traced in the West. It is not a trace of a passage, a desire to grasp and freeze the noumenon in the form, but it is the extension of the eye, it is a manifestation of the being, of the artist in his “hic et nunc”, and the action in its vitality that the viewer perceives, grasps, and is involved on the canvas by these shapes of matter rich in texture.

Furthermore, it is precisely this marking left by the artist that invites the user on the path to follow.

The winding roads that he traced represent the journey that the man – personified by the literary painter flâneur – makes in the moment of the realization of the work. Including the times of anticipation and reading of it, it guides the viewer in immersing himself in the landscape that is present with a few full-bodied or rarefied lines, now rich, now thin, now thick, now dry, juggled with rhythm and a background color. A journey in search of himself and the truth that allows him to find himself in harmony with the Universe.

A derived unity expressed through the awareness of the sign gesture, which is clearly in contrast with the idea of formal perfection and aesthetic modulor imitation of Aristotelian natured nature.

The use of the brush, therefore, is not configured as a search, a tautological praise of its medium, but as a tool capable of tracing the artist’s visual, tactile, auditory, synesthetic experiences.

This total involvement of all the senses can be read as a form of a performance, a happening, where not only the whole body of the artist is involved in the pictorial act, but also that of the spectator who must physically move to observe the artwork. This solution anticipates Picasso’s fourth dimension, the interactivity between vision and action that definitively breaks with the Western idea of painting as a staging of reality.

And this is precisely another element of comparison at a stylistic, conceptual, and philosophical level that differentiates the Western artists from the Eastern ones, since staging reality means conceiving it as something in which the human being is only a passive observer, an imitator, but at the same time, the act of appropriating the medium allows him to control the world while expressing, simultaniously, a kind of fear and terror. In Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (fig.3), the profound philosophical sense of Western romantic attitude towards nature is staged, so to speak: the traveler, seen from behind, an “en abyme” representation of the landscape gaze itself, it contemplates, in an unmistakably elegant pose, an expanse of clouds from which isolated peaks emerge, standing on a height that in turn has conquered. It is the representation of the gaze of the Western subject, an allegory of the effective domination of the world, but also aesthetic contemplation which perhaps, strictly speaking, «does not “see” anything, or little, of the nature that is in front of it in its abysmal otherness, but much it imagines and projects, delighting in stormy and dark skies, a direct legacy of the poetics of the sublime». That same point of view, from the top of a mountain for the works of the Shanshui hua, it assumes, on the contrary, a completely different meaning, and it refers to a positive sense of the possibility of an all-encompassing total vision of the landscape rather than of conquering space, the inaccessible, the distant ones.

From a philosophical point of view, this attitude of conquest on the part of the Western painter is understandable in the framework of the Faustian Stimmung of civilization, in the yearning for recognition and submission with its own physical presence; and furthermore, in any corner, any ravine, any small or huge protuberance or cavity of this Earth’s crust on which we are called to live, there is also the punishment for having dared to go further. And these are the theories that lead the German photographer of the Düsseldorf school, Gerard Richter in Berg Mountain, 1981 (fig. 4) to represent nature as a gigantic, overbearing, immobile, contemplated presence on which man cannot more to intervene because he is now a victim of his own disaster.

To recover from this disaster and to recover an ancestral relationship and communion with the universe, it is simply necessary to reconfigure the role of the artist with respect to his productions and the world.

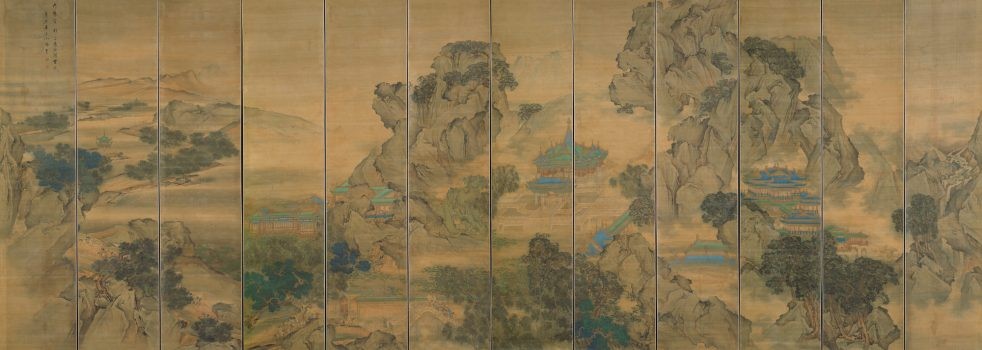

It is precisely the operation carried out by Wenren hua Hong Lei 洪磊 (Changzhuo, 1960) who, in the work Autumn Colors on the Que and Hua Mountains,《鵲華秋色》 Que hua qiuse, in 2003, he openly establishes its indissoluble bond with the tradition (fig. 4). In compliance with the VI canon of Xiè Hè, he re-proposes the visual and spatial arrangement of the elements that characterize the scroll of Zhao Mengfu 趙孟頫 (1254-1322) of 1296 – one of the cornerstones of Mountains and Water painting – but he profoundly and drastically distorts the content (fig. 5). Hong, trained in the wake of traditional Mountain and Water painting, manages in this contemporary work to reconcile the refined skills of the ancient master, combining different artistic trends, which have now given way to an agglomeration of industrial buildings with which he intends to denounce the irrepressible China’s modernization and business development process of these days.

Within the work, this operation has been possible since the same modernization (the company structures) maintains a perfectly rooted system and it coincides with the past (Mountain and Water painting). Therefore, the choice of returning to the tradition seems to play a particularly significant role in the current social context, because it offers a further opportunity of “regeneration”, recovery and reformulation of our own historical and cultural identity.

Bibliography:

Argan Giulio Carlo, G.C. Argan History of Italian Art 2 Paperback - January 1, 1977.

Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as a symbolic form, 1927, Marisa Dalai Emiliani, Abscondita, 2007

P. Fitzgerald Charles, Chinese Civilization, Enauidi 1982.

Luisa Bonesio, The evolution of the aesthetic sentiment of the Alps between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries, Lecture held in the Course Mountains have a history too, Varese, June 2002, forthcoming.

Meccarelli Marco, The aesthetics of the landscape in Chinese contemporary art, Conference in memory of Morgante Marianna, A new Chinese intellectual identity. The contribution of the Anglo-Americans through the renewal of the educational system. Master's degree course (system ex D.M. 270/2004). 2011/2012 in Languages and Cultures of East Asia

Pisu Renata, China, the rampant dragon, between modernity and tradition, a country in search of a new identity, Sperling & Kupfer (30 ottobre 2007),

Paolo Rosa, Art out of itself, Feltrinelli, April, 2011.

Shi Tao, Monk Bitter Gourd's Analects on Painting (Chinese Edition), Jouvence, 2014.

Walter Benjamin (Author) Rolf Tiedemann (Curator), Enrico Ganni (Curator), The "passages" of Paris, by Walter Benjamin, Einaudi, 2010.This article has been part of the interventions of the 25th Annual Meeting of the

International Association for Environmental Philosophy (IAEP) 2021 Conference

Read the full magazine