Ecological culture in Chinese traditional Mountain and Water painting

By; Giacomo Bruni

This article has been part of the interventions of the 25th Annual Meeting of the International Association for Environmental Philosophy (IAEP) 2021 Conference

The first four centuries of Chinese imperial history, specifically the Han dynasty, were characterized by a Confucian-based ideological setting, which gave great importance to the political and social participation of the individual. Therefore, the ideals of living a reclusive life in nature, and generally the Daoist teachings became minorities in the intellectual scene of the time. During the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties (Weijin nanbeichao 魏晉南北朝, 220-589), due to social turmoil, profound changes in social thinking were caused. With the revival of Laozi 老子 and Zhuangzi 庄子’s thinking, Buddhism also flourished, establishing a communication between Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. And once again, like during the pre-Qin period, the wild and mysterious natural environment was the object of appreciation. Intellectuals and religious personalities embraced the retired life of yinyi 隐逸 amidst the mountains, which soon led to the birth of Mountain and Water painting, shanshui hua 山水画 as an independent genre, abandoning the ancillary position towards figurative painting, which at the time was the highest form of painting. The status of independent art expression led to a production of theoretical texts, and these painting theories not only revealed the internal laws of method, history, practical and theoretical insights, but also revealed the ancient Chinese aesthetic concept towards the natural environment.

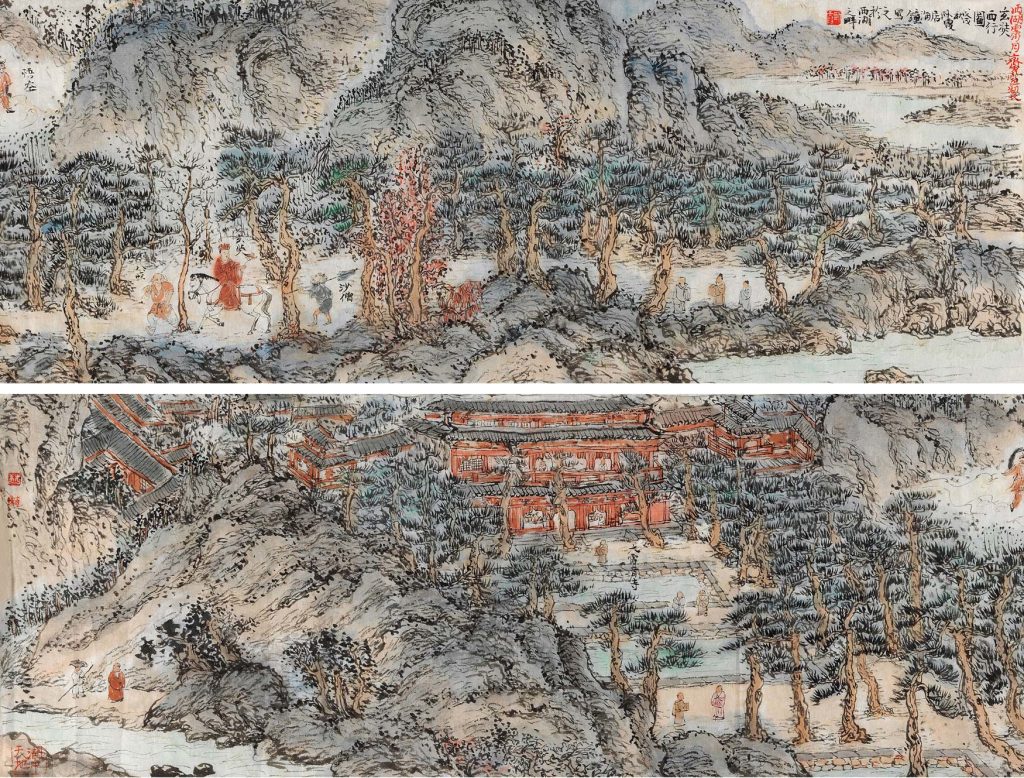

Ancient Chinese culture contains a wealth of ecological aesthetic wisdom. As a part of Chinese traditional culture, Mountain and Water painting can be said to be the most enlightening representative of the ecological spirit. In the eyes of Chinese Mountain and Water painters, the natural environment is a perceptual and transcendent world, an ideal form of beauty. An excellent Mountain and Water painting can awaken people’s senses, make them feel the ever-changing nature within, enabling them to fit into the natural rhythms of the world, so that life melts into the vitality of the universe to obtain physical and mental pleasure. It is a graphic expression of the painter’s spirit and an aesthetic relationship between men, nature, and society.

Mountains and rivers can not only give aesthetic pleasure and inspire people to create, but they also form and nourish people’s spirits. When the subject is observing the mountains and waters, through a process of empathy, its inner spirit through participation with the constant flow and changing of the cosmos (passive empathy), is consciously perfused into the object, so that the surrounding nature also has human spirit and emotion (active empathy). The two blend together, and the natural environment is alive, emotional and personified. This leads to Tianren heyi 天人合一, the unity of man and nature, which is the most important conception that takes shape in this philosophical context, that is at the base of the Chinese eco-esthetic thinking. Tianren heyi is an holistic way to live in a world that sees nature (tiandi 天地) and human beings melted in an organic connection between the three elements (sancai 三才, the sky 天, the earth 地 and the man 人) that nurtures all things, wanwu 万物. Man and nature are of the same kind, as Zhuangzi 庄子 said:

Heaven, Earth, and I were produced together, and all things and I are one. (Legge 1891)

Only when the qi 气 flows does man and nature live, interacting and influencing each other, coexisting and developing harmoniously. This status is higher than the cognitive approach, a result of the separation between subject and object (which characterizes the traditional western thinking), that sees nature as an external element that is just an object of aesthetic appreciation, or for scientific research purposes, etc. In order to reach this status, it is necessary to be in direct contact with nature.

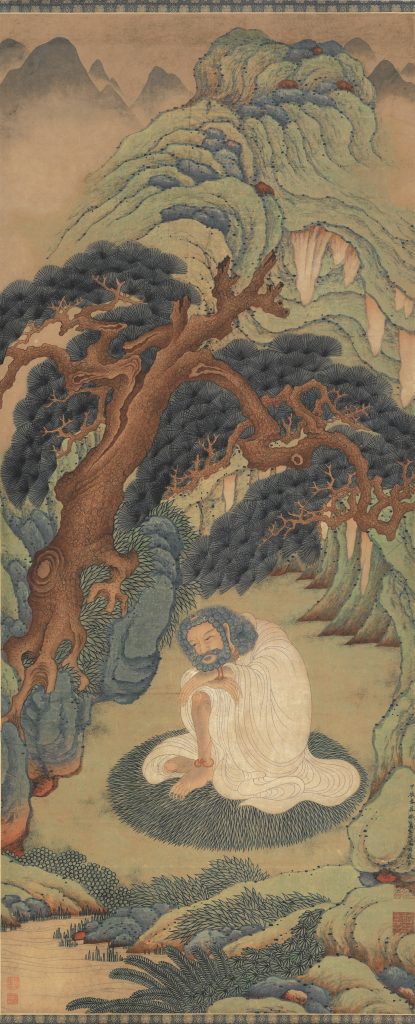

Since the pre-Qin period, Chinese scholars had developed and promoted the movement of the reclusive culture, yinshi wenhua 隐士文化, an important branch of Chinese traditional culture with distinctive characteristics and far-reaching influence, till the contemporary times. From the womb of this very cultural approach, Mountain and Water painting was born, as an independent genre that was born in close relation with Daoist theories, Xuanxue thinking and Buddhist practice.The mountains and wild forests became places of threshold where the concepts of space and time disappeared, where the existential modalities of reclusive culture can be fully applied, in order to reach higher levels of union with the natural world, an intimate relationship. Daoism thinking believes that this kind of harmony eventually leads to the Dao 道, the “Way”, and only with a clear mind/heart is it possible to reach the highest aesthetic realm. Harmony has become the basic requirement of Chinese art.

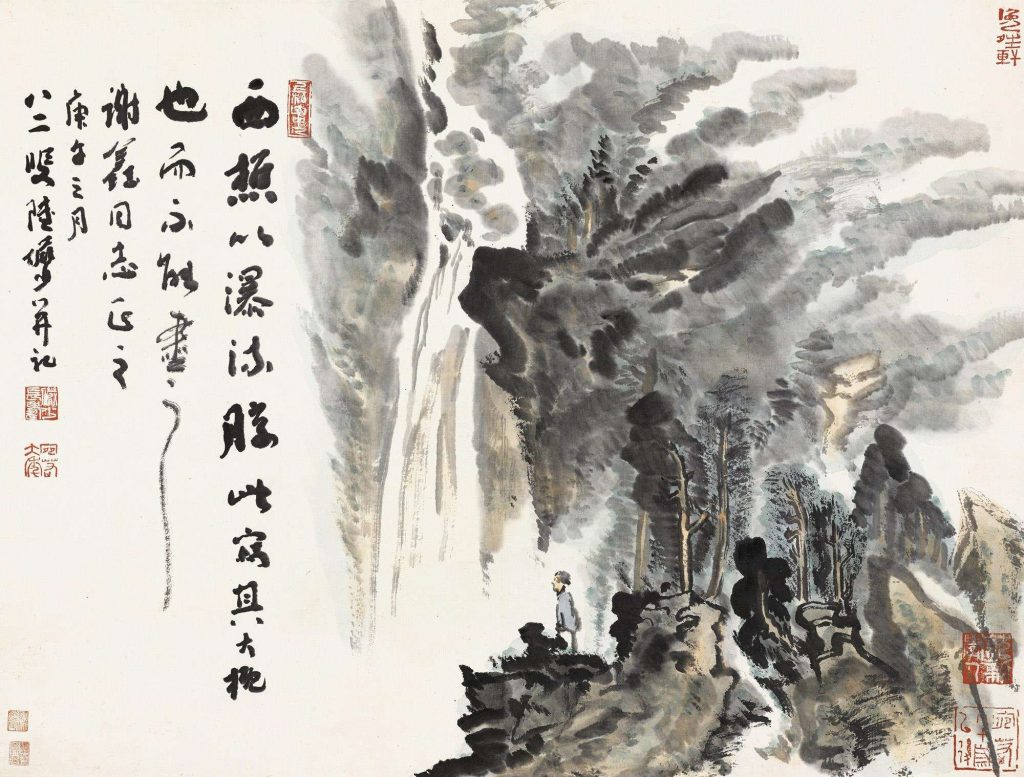

In order to reach this realm, the painter must work hard on a technical level, as well as strengthen his own spiritual cultivation. Observing the natural environment is not only an aesthetic act, but also a means of self-cultivation and purification of the soul. It eliminates the utilitarian contradiction between humans and nature, by forgetting the secular life, material needs and thirst for fame and success, and to let the subject participate in the flowing of qi. The creation process of the painting is to express the beauty of nature, as well as to build a spiritual home and realize the ideal of aesthetic dwelling. Shanshui hua is the graphical expression of harmony between man and nature in order to allow woyou 卧游, to travel within the mind, and live the aesthetic experience of nature without having to physically be there.

The common goal of these theoretical texts is to improve the relationship between man and nature; revealing the secrets of the wild mountains and waters to those who live in the society and the secular world, to give anyone the possibility of experiencing the union between man and the natural environment.

Since the birth of this art expression, these conceptions are at the base of theoretical production that is still vivid in our time.

Zong Bing’s Hua shanshui xu

Zong Bing 宗炳’s (375-443), Introduction to Mountain and Water Painting, Hua shanshui xu, 《画山水叙》is an extremely dense and short text, which reveals for the first time the secrets of Mountain and Water painting and the reasons why we should practice it. It lays down the foundations for the evolution of this artistic practice, touching conceptions regarding Mountain and Water paintings that are going to be developed by the future generations.

Following the mainstream of the reclusive culture of his time, Zong Bing was himself a hermit at Mount Lu, Lushan 庐山 devoted to Buddhism, and a disciple of Hui Yuan 慧远 (334-416).

Following the Zhuanglao 庄老 thinking, he regards mountains and rivers as the embodiment of Dao, and forgets himself in the appreciation of the natural environment, entering in a complete aesthetic state to reach the union of mind and body. The Hua shanshui xu is his aesthetic appeal to nature:

The wise men follow the Dao in their souls, and the virtuosos men captivate Dao by the form of the landscape (Siren 1971)

He believes that natural scenery has the ability to reveal the Dao.

The formation of the artistic conception of Mountain and Water painting is the artist’s thoughts and emotions integrated with the essence of the mountains and rivers.Through depersonalisation it’s possible to express the harmony and unity of the subject’s internal world and the external nature. The reflection of this “unity” in the artistic production shows that the painter’s self-personality realizes the fusion and resonance of the object and the self, in correspondence with the natural environment and natural aesthetic value.

In order to reach this state of mind, the tranquillity of the heart xin 心 (mind, soul) that unites external vision and internal perception is fundamental.The state of tranquillity is characterized by emptiness and quietness xujing 虚静, more easily reached in a situation of isolation from society. It creates a synchrony and harmony between the natural environment and the most intimate part of the subject. Only then will it be possible to see/perceive the reality of things, breaking the barriers of space and time, achieving happiness. This recalls Zhuangzi’s concept of zuowang 坐忘, sitting and forgetting:

My connection with the body and its parts are dissolved; my perceptive organs are discarded. Thus leaving my material form, and bidding farewell to my knowledge, I become one with the Great Pervader. This I call sitting and forgetting all things. (Legge 1891)

Zong Bing introduced the concept of woyou, to travel within the mind by looking at a painting, a spiritual journey shenyou 神游 which leads the observer to experience a state of happiness and perception of the Dao. In the final section of the Introduction to painting of Mountains and Waters, Zong Bing writes:

In moments of relaxation, after having put my mind in order, after emptying a glass of wine or strummed the lute, I unroll a painting and sit in front of it, and without leaving the crowded houses of men I find myself wandering in solitude, in wildlands, with no trace of human beings. Mountain peaks rise above the mists and clouds, gorges and forests extend into the distance. The wise and virtuous shine from antiquity, and all the interesting aspects of life come together in the mind. What else do I need? Being in this state I am happy and delighted, what more can I ask for? (Translation mine)

Guo Xi’s Linquan Gaozhi

Linquan Gaozhi 《林泉高致》 is a theoretical work about Mountain and Water painting written by Guo Xi 郭熙 (1020-1090), a painter of the Song Dynasty. It embodies many ideas about the relationship between man and the environment, and reveals rich ecological aesthetic wisdom. Following the conception of Tianren heyi, Guo xi wants to prevent the separation and estrangement between man and the natural environment and improve the relationship between the two, engaging also on an emotional level.

Human sentiments colour the scene. Thus men feel happy when facing the spring hills covered with mists ; they feel relaxed and at ease facing a summer hill within deep forests, feel alert and lonely against an autumn hill, clear and sparse with an abundance of falling leaves, and feel silent and desolate against a winter scene enveloped in banks of dark fog. A painting should make one feel these sentiments as if one were bodily there. (Lin Yutang, 1967)

Guo Xi, owing to his humanistic Confucianist thinking, had the need to reach those living in the society, this was because according to Confucian thinking, in times of peace and prosperity, the man has to give his support to the society rushi 入世. Therefore, he proposed an alternative to the retirement from a secular world yinyi 隐逸. Guo Xi used the idea of woyou in order to connect those who can t live on the mountains, to nature, a spiritual retirement within the society:

It is in human nature to feel the hustle and bustle of society and desire to see spirits and immortals hidden in the clouds. In times of peace, under a good emperor and excellent parents, it would be wrong to leave to be alone, because there are duties and responsibilities that cannot be ignored […]. The dream to retreat in the forests and springs and to find oneself in the company of clouds and mists is always there, but the eye and ear are deprived of it. Now a good hand has reproduced them for us. Without leaving your room you can imagine yourself sitting on the rocks in a gorge, listening to the screaming of monkeys and bird songs; while the light of the mountains and the colours of the water dazzle the eyes. Isn’t it a joy, a realization of a person’s dream? This is why mountain and water paintings are so in demand. Approaching these paintings without the necessary mood would mean ruining this magnificent view and clouding the refreshing breeze. (Lin Yutang, 1967)

Another way to connect man with the natural environment is the theory of sike 四可, the four ways of experiencing nature. Guo Xi writes:

It has been truly said, that among the landscapes there are those fit to walk through [可行], those fit to contemplate [可望], those fit to ramble [可游] in and those fit to live [可居] in. All pictures may reach these standards and enter the category of the wonderful; but those fit to walk through or to contemplate are not equal to those fit to ramble or to live in it. (Siren, 1971)

Keju keyou 可居可游 is the best way to experience the mountain, in solitude living and travelling among them, and kexing kewang 可行可望 is the way to experience it for those who can’t live in the mountains, for the men of the secular world looking for a break from the material life, a similar concept to what we now call tourism.

A way to eliminate the distance between man and nature is by changing the way we look at the natural world. We shouldn’t look at it as a stranger, or a different and separate entity, but we should accept nature as if it’s a human being, because a relationship with nature is fundamental to cultivate the mind:

Streams are the blood veins of a mountain, the vegetation its hair, the clouds and mists its expression. Therefore, a mountain becomes alive with water, luxuriant with bushes and trees, and graceful with clouds. A mountain is the face of a stream, water- side pavilions are its eyes, and fishing activities its expression. Therefore a stream becomes graceful with hills by its side, clear and pleasant with pavilions, and poetic with the presence of fishermen. Such should be the disposition of mountains and streams. (Lin Yutang, 1967)

By giving the mountains and rivers a personification, forests, springs and valleys become the externalization of human beings, and at the same time they were given the norms of “rituals” li 礼 that originally belonged to the human society. As a result, the norms of human society have also become the norms for the composition of Mountain and Water paintings and the layout is impregnated with moral meanings.

A central mountain serves majestically as the lord of the smaller crests and forests and ravines grouped around it, the eminent point of everything big and small within the compass. Its demeanour is like that of a king receiving the homage of his courtiers and subjects, none daring to assume easy-going or disrespectful postures. A tall pine rises straight into the sky, the leader of all bushes, creepers and vegetation grouped around it, like a commander. Its demeanour is that of a gentleman in a position. (Lin Yutang, 1967)

Conclusion

The artistic dimension, the human dimension and the natural dimension as a whole system, are the focus of ecological aesthetics. Mountain and Water paintings are useful for alleviating the tensions and contradictions of contemporary people towards nature, society, and other people. Ecological aesthetics observes both the natural and spiritual realm.The appreciation of Mountain and Water paintings makes people forget their worries, cleanses their hearts, makes the viewers spiritually satisfied, and finally reaches the highest state of the unity of nature and man.

Zong Bing believes that people should get close to nature so that they can cultivate calmness and self-adjustment in the natural aesthetic appreciation of mountains and rivers. This state of mind helps to improve the relationship between men and the cosmos.

Guo Xi’s text is permeated with ecological aesthetic wisdom of respecting nature, being close to nature and caring for nature. It is full of insights and enlightenment for the current ecological civilization and aesthetic systems reaching anybody who wants to engage in this way of living, even for those who are unable to live outside of the secular world.

These ancient texts are extremely illuminating for our contemporary ecological problems, the concept of harmony and unity between man and nature has a major role in the construction of modern ecological civilization, overcoming the sole cognitive approach and the separation between subject and object.

Harmony is the key concept in this vision of the world, not just the harmony between man and the natural environment, but also harmony in the theoretical thinking that leads to a philosophical syncretism. Different approaches can cooperate in order to create a complex system to answer the common questions about the cosmos, how to relate with it and to know our place in it, in order to reach a higher level of existence that crosses the barrier of the physical and material world.

With a holistic vision of the cosmos, the man has to learn how to relate with the natural environment, without exploiting it or annihilating the human nature, acting with righteousness (yi 义 of the Confucian thinking) in order to improve the environment, but at the same time we need to understand the possible repercussion of our actions and follow the natural order of things (wuwei 无为 of the Daoism thinking). This is possible just when the man treats nature as his own kind, with empathy, in harmony.

Like Zong Baihua 宗白华 (1897-1986) said: “the wisdom of the East is not to fly above nature and conquer it, but to dive deep into the core of nature and experience it, connect with it, and nurture it as universal love.”

Bibliography

Sirén, O. (1971). The Chinese on the art of painting. New York.

Lin, Y. (1969). The Chinese theory of art: Translations from the masters of Chinese art [by] Lin Yutang. London: Panther Books.俞剑华 Yu, J. (2011). 《中国古代画论精读》 Zhongguo gu dai hua lun jing du. 人民美术出版社 Rénmín měishù chūbǎn shè.

王万发, 何颖 Wáng W., Hé Y.《’林泉高致’ 的生态审美智慧》Línquán gāo zhì’ de shēngtài shěnměi zhìhuì, 《文艺评论》Literature and art criticism 2012·6 车荣晓, 戚静 Chē R., Qī J.林泉高致《蕴含的儒家生态美学观念论析》Línquán gāo zhì` yùnhán de rújiā shēngtài měixué guānniàn lùn xī, 《人文天下》 rénwén tiānxià, 2019·150

王万发 Wáng W.《从‘画山水序‘看中国山水画的生态审美观》cóng ‘huà shānshuxù ‘kàn zhòng guó shānshuhuà de shēngtài shěnměi guān 《铜仁学院学报》 tóngrén xuéyuàn xuébào 2008·10/5

Read the full magazine