Gao Jianfu: Painting Style & Signatures

Issue 2 – By; Zhu Wanzhang 朱万章

Translated by; Giacomo Bruni and Claudio D. Lucchi

Gao Jianfu 高剑父 (1879-1951), born in Panyu (Guangzhou) in Guangdong province, was one of the founders of the Lingnan School of Painting 岭南画派. His birth name was Lin 麟, but he would later use various literary names, such as Lun 崙, Jue Ting 爵廷, Lao Jian 老剑, Jian Lu 剑庐. In the eighteenth year of the reign of Guangxu (1892), he studied painting under the flower-and-bird painter Ju Lian 居廉 (1828-1904), and began to learn the painting methods of flowers and plants 花卉, wild grass and insects 草虫, thus acquiring the foundations of traditional Chinese painting. In the twenty-fifth year of Guangxu (1899), Gao Jianfu continued his studies under the guide of his close friend and former learning companion, Wu Deyi 伍德彝 (1864-1928). The Wu family was a prominent family in Guangzhou in the late Qing Dynasty, and Wu Deyi’s father, Wu Yanliu 伍延鎏, was also a painter. He had the possibility of study pictorial and calligraphic works of famous masters of the past. Gao Jianfu’s study under Jian Lu enabled him to master the flower-and-brd painting mogu 没骨 (boneless) technique, developed by Yun Nantian 恽南田 (1633-1690) in the early Qing Dynasty. However, Gao Jianfu was not satisfied with the sole learning of traditional painting. Later, with his brother Gao Qifeng 高奇峰 (1889-1933), Chen Shuren 陈树人 (1884-1948) and others, he moved to Japan to continue his artistic studies. During the short time they spent in Japan, they familiarised themselves with the unique pictorial techniques of Nihonga 日本画[1], also commonly known as Japanese painting, and applied them to Chinese painting. This undoubtedly innovative artistic exploration made it the forerunner in modern art history and established its position in the history of art. They combined the rendering of the environment and the contrast of light and shadow of Nihonga painting with traditional Chinese painting in order to create a fresh and natural artistic style. This kind of Chinese painting with unique visual effects was at that time called “new school of painting” 新派画 or “eclectic painting” 折衷画. That particular painting style that was later to be defined by academic circles as the “Lingnan School of Painting” by academia refers to this concept of “eclectic painting”.

After Gao Jianfu and Gao Qifeng returned to China, they started to promote this emerging form of Chinese painting in various ways in order to expand its influence, among others through the establishment and publication of the True Pictorial 《真相画报》and other related editorial projects, and began for the first time to hold exhibitions in China. Just as the emergence of many new things always meets with all forms of resistance, Gao Jianfu’s artistic attempts were attacked and criticised by various forces from the beginning because of the evident influence of Nihonga painting to be found in it. Some people went as far as to call it the “opposite force”, deeming that it deviated from the orthodoxy of Chinese painting, thus insulting the academic tradition of Chinese painting. However, as the number of members of the Lingnan School of Painting continued to grow and their painting styles matured, their innovative spirit set on improving Chinese painting and the tireless promotion of the Gao brothers and their followers gradually caused Gao Jianfu to become more and more popular. The attention of the artistic world gave the Lingnan School of Painting a relevant historical status. To this day, when we investigate Chinese painting in the first half of the 20th century, the Lingnan School of Painting established by Gao Jianfu, Chen Shuren, and Gao Qifeng, has become an indispensable and important school. The key role they held in the context of the artistic innovation movement in the 20th century is commonly recognised in modern art history.

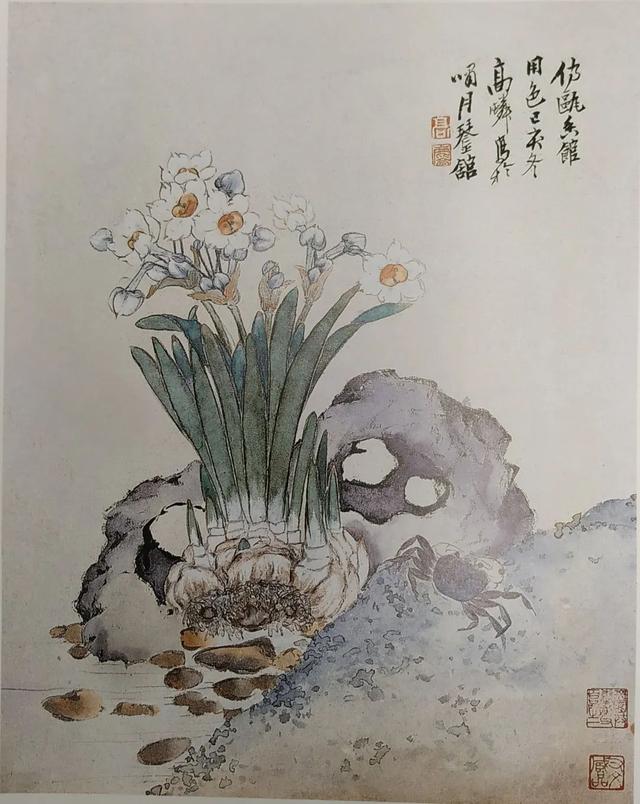

Most of the extant works by Gao Jianfu that are now on display were made after his return from Japan, at a time when his style had already begun to change. Therefore, it can be said that these works testify to an already stable artistic style. But when examining Gao’s style of painting, we cannot ignore the influence of his early Ju School 居派 style. In Gao Jianfu’s early works, a traditional artistic tendency is evident. Some examples from this period are Two birds and crape myrtle 双鸟紫薇 (1899), Flowers, birds and insects in the manner of Luo Liangfeng 仿罗两峰花鸟草虫, Narcissus, Crab and Stone in the manner of Yun Shouping 仿恽寿平水仙蟹石, Bird and Flower 花鸟 (1900), Copy of the Song Painting Lotus Pond and Grasshopper 临宋藕塘芙蓉蚱蜢 (1901) and Portrait of a Wealthy Person 富贵图. These works draw their influence from various sources, such as Yun Nantian’s boneless flowers or Luo Pin’s 罗聘(1733-1799)”weird” 怪异 flower-and-bird paintings, and the style of rendering flowers and plants through Ju Lian’s techniques of zhuangfen 撞粉 and zhuangshui 撞水 — two different ways of applying washes of ink, water and colour on paper. Others are copies of ancient masterworks and as a result, they embody profound traditional skills. For example, in Narcissus, Crab and Stone in the manner of Yun Shouping 仿恽寿平水仙蟹石 ,

the daffodils are painted with mogu technique and light colours, the brushwork is precise, the outline of the stone is exquisite, executed with a meticulous brushwork reflecting the brushwork of ancient masters. In the works of this period, we may see the elevated artistic skills of a Chinese painter and his ability to understand and assimilate ancient paintings. It is obviously unscientific to assert that so-called “eclectic painting” is completely unrelated to “orthodox Chinese painting”. The academic system that attacked Gao Jianfu’s works, accusing him of forgetting his ancestors, denotes a fundamental lack of understanding of Gao’s early works. Of course, had Gao Jianfu been satisfied with such works, perhaps modern Chinese painting history would merely treat him as one more mediocre Chinese painter since, artistically speaking, the above-mentioned value is only reflected inside the sphere of Chinese painting, in the cultivation of traditional painting skills and techniques.

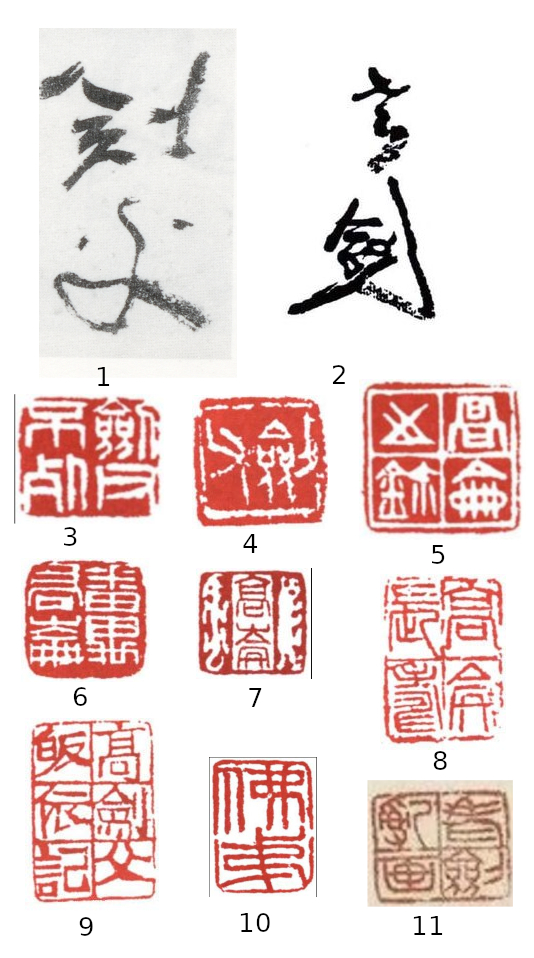

Generally speaking, Gao Jianfu’s works from this early period are often signed “Gao Lin” 高麟, “Noble Hall”, Jue Ting 爵庭, “Magpie Pavilion”, Que Ting 鹊亭, “Lin” 麐. During this period, other people would often add the colophons on Gao’s works, offering them gifts, mostly using in such cases the name “Jue Ting” 爵庭. The seals appearing on the works of this period are: “Gao Lin” 高, “Jue Ting” 爵庭, “Lin’s Seal”, Lin Yin 麐印, “Gao Lin’s Seal”, Gao Lin Zhi Yin 高麟之印, “Xiao Yue Qin Guan” 啸月琴馆 carved in (i.e., not in relievo) characters on square-shaped seal; “Long Live Gao Lin”, Gao Lin Changshou 高麟长寿, “Jue Ting”

爵庭, “Lin’s Seal”, Lin Yin 麟印, “Que Pavilion”, Que Ting 芍亭, “Addicted to painting”, Hua Pi 画癖 in relievo characters on square-shaped seal; and “Gao” 高, “Lin”

麐 featuring both carved in and in relievo characters. A connoisseur cannot fail to know these seals. If divided by time periods, these works were created roughly before 1905, especially while he practiced painting under Ju brothers 居氏. Compared with Gao Jianfu’s other periods, such works are relatively rare, hence more valuable to collectors.

Gao Jianfu’s early calligraphy was also more rigorous. His calligraphy is dignified and beautiful, and his individual inscriptions even show some traces of guange ti 馆阁体 (official script), which concord with his painting style of the same period.

What really established Gao Jianfu’s dominant position in the painting school is that he combined the painting language of Japanese painting and the influence it had absorbed from Western painting concepts, in order to transform and revolutionise Chinese painting, thus forming a relatively stable style. This style was followed and passed on by his students.

Gao Jianfu’s works may be roughly divided into two stages:

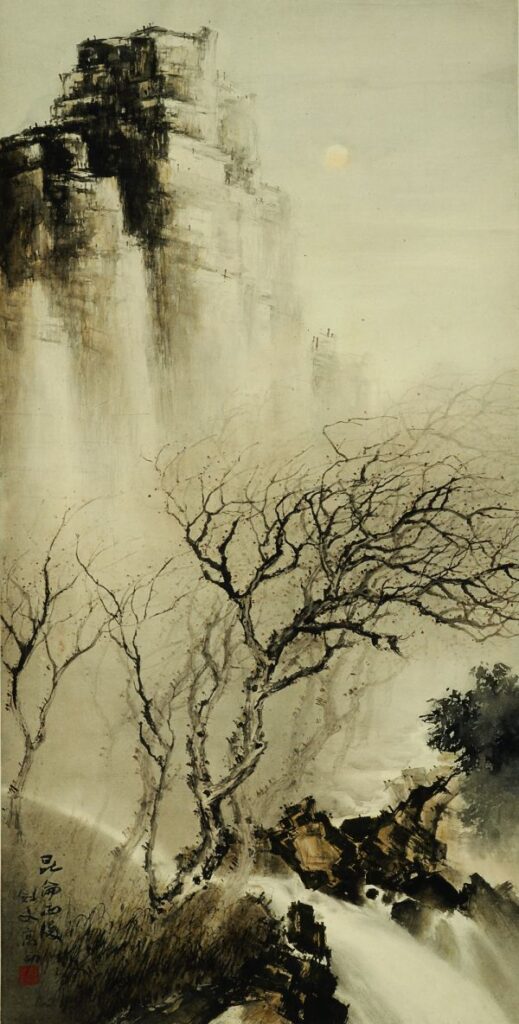

The first stage lasted from about 1905 to the late 1920s. During this period, Gao Jianfu studied in Japan and was influenced by the artworks of neighbouring countries, where painting was shaken by these new styles and techniques. He tried to apply such techniques to his own creation. Therefore, in his works, the Japanese painting style is the most obvious, and it was also the most attacked by his “political enemies”. Most of these works are based on realism, with bright colours. The figure painting Luofu Fragrant Dream Beauty 《罗浮香梦美人》

and the mountains-and-waters painting Kunlun after the Rain 《昆仑雨后》are typical examples.

The clothes patterns, hair buns, costumes, and the hazy moods of the characters in the first are typically Japanese in their rendering, while the latter shows the mist, water vapours, mountains, streams, and the damp and refreshing breeze after the rain. The atmospheric representation is a technique commonly used by Japanese painters since the 19th century. Some scholars pointed out that the paintings of this period were entirely influenced by one particular Japanese painter, or a part of a certain painting was directly copied from a work of a Japanese painter, as some expressional methods were exactly the same as created by these painters. Some even thought that many of Gao Jianfu’s paintings are in fact “patchworks” of the paintings of one or more Japanese artists. Some of his enemies also suggested out that some of these works were actually paintings without inscriptions bought on the streets of Japan, which were “used” by Gao, who simply added his own inscriptions and name. Of course, constructive criticism demonstrates that such assertions are unreasonable. The traces of copying in Gao Jianfu’s works of that time are obvious. As for the accusations of so-called “plagiarism”, in addition to Gao Jianfu himself, many people also wrote articles to clarify this point, believing that history would eventually do Gao Jianfu justice, which is why I will not repeat them here. Of course, these “problems” are all “searchings” or “weaknesses” that a painter in the stage of innovation and exploration cannot avoid, but they do not hinder our understanding of his status and correct evaluation of his painting skills.

Gao Jianfu’s second stage was from the late 1920s to the 1950s, and saw his artistic activities concentrate mainly in Shanghai, Guangzhou, India, and Macau. This period saw large social turmoils (such as the Sino-Japanese War, the Civil War, etc.) — historical changes which undoubtedly exerted a certain influence on his artistic style.

In terms of technique, he abandoned the dominant expressionist techniques of Nihonga painting, and returned to a limited extent to the Chinese tradition, and blended the two organically. Therefore, in the mountains-and-waters paintings, we can see both the brushwork and the environmental and atmospheric effects of Japanese paintings as well as the axe-cut texture stroke 斧劈皴 and hemp-fiber strokes 披麻皴 of the Song Dynasty, such as in the Lonely Fishing in the Wind and Snow《风雪独钓图》, now in the collection of the Guangdong Museum, the close-up view of the old man, the trees and the misty atmosphere bear a Japanese mark, while the distant mountains are rich in traditional dotting and texturing techniques. The flowers, the stones and grasses used as the lining of the scenery are smudged with watercolours and gouaches. At the same time, they are also mixed with water and ink, and the flowers display the use of Yun Nantian’s mogu technique. The subjects of figure paintings from the previous period, which mainly focused on meticulous depicted ladies and focused on expressing the environment and atmosphere have now disappeared. In their stead, there are now mainly freehand Buddhist figures. The brushwork appears careless, but is in fact imbued with great originality, as may be seen in the figure paintings Gao Jianfu created after returning from India, such as Bodhidharma, Luohan, Guanyin, etc.

In terms of painting themes, the repertoire has become more extensive. There are not only mountains and waters, flowers and birds, and characters that express traditional themes, such as Begonia 《海棠图》, Ink Bamboo 《墨竹图》, Autumn Mountain Master《秋山高士图》, etc. (all collected by the Guangdong Museum), but also modern lifestyles that reflect realistic care themes that traditional Chinese painters pay less attention to, such as wars, famines, or realistic tourist destinations, such as Cold Smoked Isolated City 《寒烟孤城图》 (Collection of the Guangdong Provincial Museum), Flame of the East Battlefield (Collection of the Guangzhou Art Museum), Burmese Buddhist Relics 《缅甸佛迹》 (The Cultural Relics Collection of The Chinese University of Hong Kong), etc.

In terms of artistic conception, the author now uses freehand brushwork 大写意 to show a reckless, unrestrained and incisive attitude. Some commentators believe that his paintings are tenser than Gao Qifeng’s and Chen Shuren’s, mainly referring to the style of painting of this period. Among these may be mentioned Looking afar from the tower《倚楼极目图》 (collected by the Tianjin Museum),

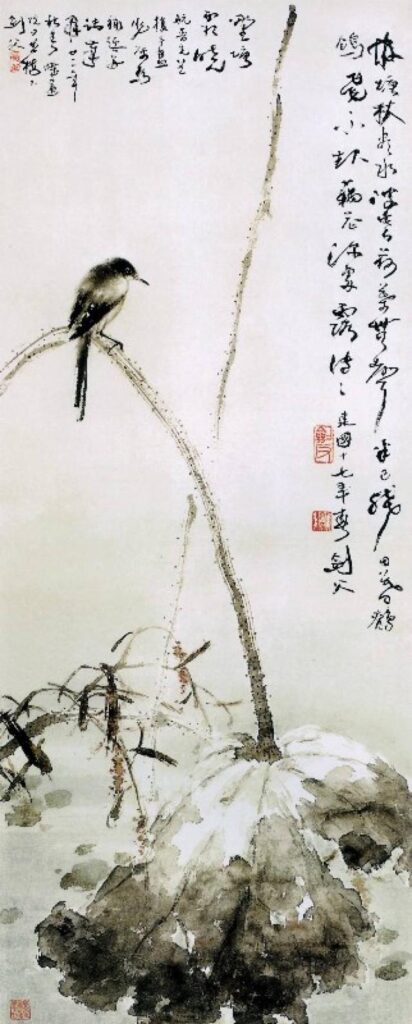

Remnant Lotus and Wagtail《残荷鹡鸰图》

Two Eagles 《双鹰图》 (all collected by the Guangdong Museum), etc. Obviously, regardless of technique, subject matter, or artistic conception, the painting style of Gao Jianfu during this period has matured, and he has become familiar with the handling of his painting environment, gradually forming a qualitative and unique character. Gao Jianfu set up apprenticeships in Guangzhou, Macau, Hong Kong and other places, and served as a tutor of Chinese painting at the Sun Yat-Sen University, which allowed him to spread his painting style and become famous, thus becoming a leader of the Lingnan School of Painting.

The calligraphic style of this period is also completely different from the earlier period. His calligraphies appear in vivid cursive scripts in inscriptions, couplets, plaques and even books inscribed for friends. The strokes vary from thick to thin, and ink tones from thick to light. Vertical brush strokes are like old vines, while horizontal brush strokes are like dying branches. The brush appears clumsy, but in fact it is lively and unique. Gao Jianfu’s calligraphic style, which appeared in the middle and late stages of his career with a weird and crazy mood, has been defined “withered vine” 枯藤体 by some commentators. Although it is said to be “dry”, it does not lack in vitality, thus forming a vigorous and unique personality. Although Gao Jianfu is not famous for his calligraphy, his unique withered vine style is not uncommon even if it is placed in the group of modern calligraphers.

The signatures he used during this period are also different from his earlier ones. They mainly include “Panyu Gao Lun”番禺高崙, “Gao Lun”高崙, “Gao Jianfu”高剑父, “Jianfu”剑父 (1-2 in Seals and signatures), “Lun”崙, “Jian”剑 (Sword), “Ajian”阿剑, “Master Jian”剑公, “Kunlun Mountain Dweller”昆仑山民, “Kunlun Mountain Farmer”昆仑山农, “Old Jian” 老剑, etc. The commonly used seals are also richer than the earlier ones. In addition to the general name and character size, there are still many decorative seals (xianzhang 闲章) that record personal mood, behaviour, and interests. According to the author’s preliminary statistics, these seals have rectangular shape and the characters are carved in (i.e., not in relievo, 白文): “Gao Lun Longevity”高仑长寿, “Jianfu” 剑父 (4) and “Gao Lun’s Seal” 高仑之鉨; carved in and in square shape:”Gao Lin” 高麟[2],“Cheerful Gao Lun” 高仑高兴, “Lingnan Jianfu” 岭南老剑, “Pick up the brush and look around the world” 提笔四顾天地窄, “Master Jian”剑公, “Jianfu’s Work after Twenty (years)” 剑父二十以后之作, “Jianfu’s Work after Thirty (years)”剑父卅后所作, “Jianfu’s Poems, Paintings and Calligraphy”“剑父诗词书画”; “Jianfu’s Seal” 剑父之鈢(5), “Immortal Jianfu”剑父不死 (3)etc.[3]; in relievo 朱文, on oval-shaped seal: “Old Jian”老剑; in relievo on round-shaped seal: “Lun”仑; in relievo on square-shaped seal “Jianfu” 剑父, “Jianfu”剑甫etc.[4]; in relievo on rectangular-shaped seal “Gao Painter” 高画士, “Gao Jianfu Conversion Record” 高剑父皈依记(9), “Buddha disciple”佛弟(10)etc.[5]; featuring both carved in and in relievo characters: “Panyu Gaolun Seal” 番禺高仑之印.

Gao Jianfu’s painting style has been carried forward through the inheritance of his followers. Like his master Ju Lian, he exerted a huge influence in the Lingnan painting circle. Among these disciples, many later became the backbone of the 20th century Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao painting circles, such as Fang Rending 方人定 (1901-1975), Su Woonong 苏卧农(1901-1975), Li Xiongcai 黎雄才(1910-2001), Guan Shanyue关山月(1912-2000), Si Tuqi司徒奇(1904-1997), Yang Shanshen杨善深(1913-2004), etc.[6] Although their style of painting is far from the original “Eclectic School” period, as the artistic descendants of Gao Jianfu, they have become the main representatives of the contemporary Lingnan School of Painting.

The Author:

Zhu Wanzhang 朱万章, born in Meishan, Sichuan, graduated from the History Department of Sun Yat-Sen University中山大学 of Guangzhou, and the Chinese National Academy of Arts 中国艺术研究院, in Beijing, with a doctorate degree. He is currently a research librarian of the National Museum of China 中国国家博物馆 and a member of the Theory Committee of the Chinese Artists Association 中国美术家协会. He is engaged in the collection of works of Chinese calligraphy and painting, art history research and art review. He is the author of more than twenty volumes such us: Calligraphy and Painting Appreciation and Art History Research《书画鉴考与美术史研究》, Focus on the History of Painting and Calligraphy Appreciation and Collection《销夏与清玩:以书画鉴藏史为中心》, Authenticity and Falsification of Calligraphy and Painting《书画鉴真与辨伪》, Records of Paintings《鉴画积微录》, On Calligraphy and Painting in the Ming and Qing Dynasties《明清书画谈丛》, A Collection of Books on the Centennial Painting Garden

《尺素清芬:百年画苑书札丛考》, A Study of Painting and Calligraphy Appreciation Since the Song and Yuan Dynasties《过眼与印记:宋元以来书画鉴藏考》, Meeting in Paintings: A New Record of Artistic Events in the Past Hundred Years《画里相逢:百年艺事新见录》, The Universe Beyond the Painting: Notes on Calligraphy and Painting Collection Since the Ming and Qing Dynasties《画外乾坤:明清以来书画鉴藏琐记》.

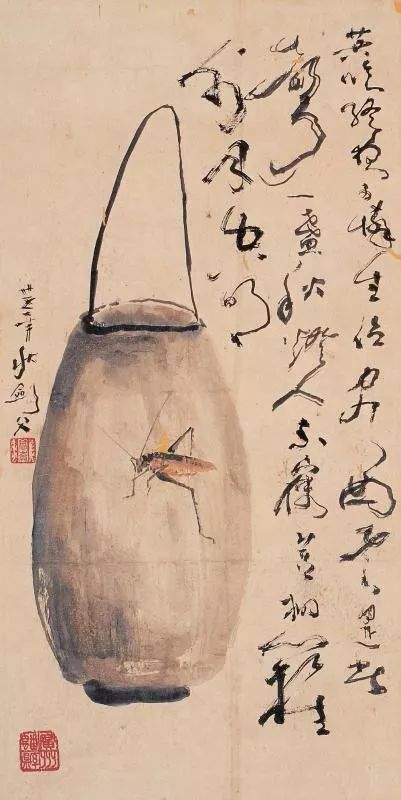

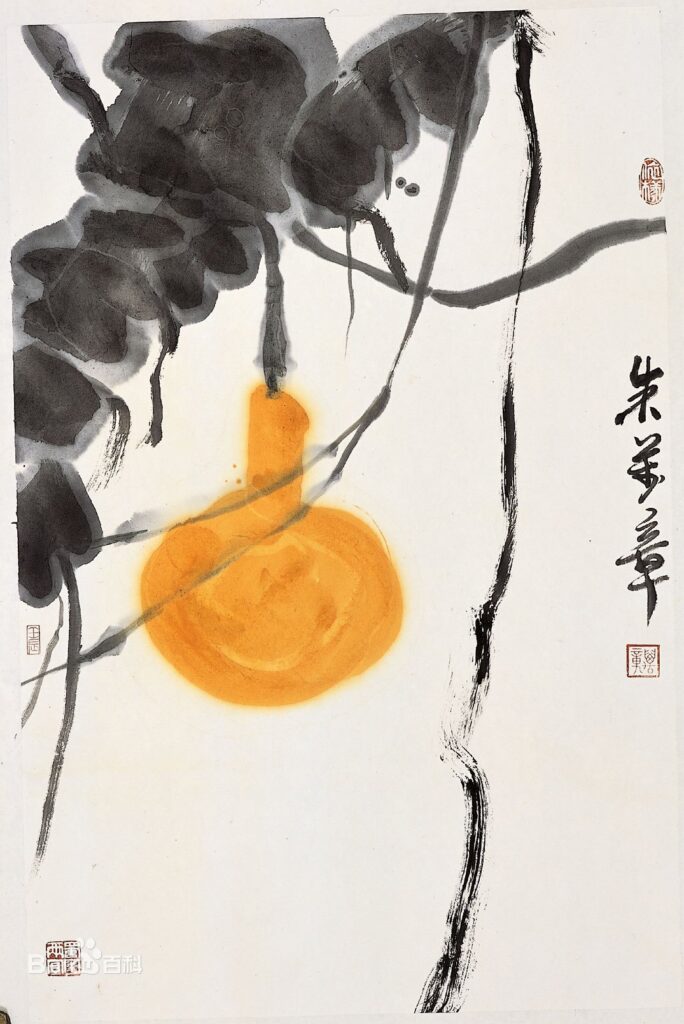

Zhu Wanzhang is also known as a painter and reputed for his depictions of gourds. Various albums regarding his works have been published like: One Gourd and One World: Zhu Wanzhang’s Painting Collection《一葫一世界:朱万章画集》, and Study and Art: Zhu Wanzhang and His Art World《学·艺:朱万章和他的艺术世界》.

Gourd 《葫芦》

Read the article from the magazine

[1] A painting movement born at the end of the 19h century who attempted to oppose Meiji Japan’s infatuation with Western culture such as the Yanghua 洋画, “Western-style painting”. Nihonga painters weren’t insensible to Western pictorial ideas.

[2] Except for this one, the seal used by Gao Jianfu in the early days was almost never seen again. This is something we need to pay special attention to when identifying his paintings.

[3] “番禺高仑”(6)、“高仑之鉨”、“说到人情剑欲鸣”、“高蹈独往萧然自得”、“男儿生不成名身已老”

[4] “高仑长寿”(8)、“剑父不死”、“仑之鈢”、“广州番禺县”、“剑父旅申时所画”、“高剑父马背船唇朱记”、“老剑乱画”(11)、“乱画哀乱世也”、“剑父”、“旅行纪念剑父持赠”

[5] “高仑”(7)、“剑父”、“游艺中原”、“人共江山老”、“仑翁”

[6] Zhao Chongzheng赵崇正(1910-1968), He Lei何磊(1916-1978), Li Fuhong 李抚虹(1902-1990), Wu Peirong伍佩荣(1910-1979), Luo Zhuping罗竹坪( 1911-2002 )