Notes on Cai Liang’s Paintings

Issue 1 – Author: Giacomo Bruni

Wenrenhua, (Chinese: “literati painting”) refers to an ideal form of the Chinese scholar-painter who was more interested in personal cultivation and expression than in literal representation or an immediately attractive surface beauty. First formulated in the Northern Song period (960–1127)—at which time it was called shidafuhua 士大夫画 by the poet-calligrapher Su Dongpo 苏东坡 – the ideal of wenrenhua was finally and enduringly codified by the great Ming dynasty critic and painter Dong Qichang 董其昌 .

According to the principle of wenrenhua, the completely literate, cultured artist—learned in all the humane arts—who revealed the privacy of his vision in his painting was preferred over the “professional,” whose paintings were more obviously pleasing to the eye. The contrast is overly categorical, but it is useful still in understanding the major interests and intentions of Chinese painters through the ages.

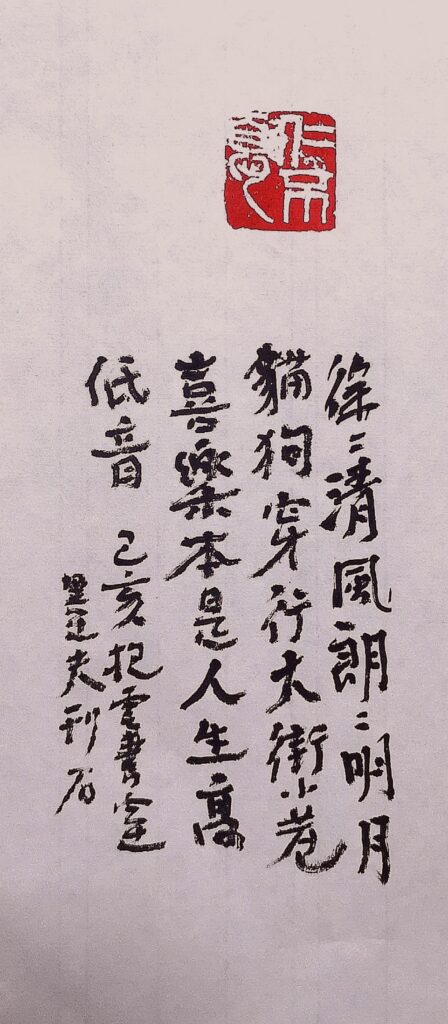

Cai Liang, is a thriving young artist from Guangdong province in Dianbai city. His artistic name is Mofu 墨夫, this name represents his desire to grow old in the company of the ink, in other words to never stop practicing painting and calligraphy during his life time. He is both a painter and an art educator based in Zhongshan city. Cai Liang learned Chinese mountain and water painting and it’s theory from his early studies. He also mastered in western oil painting techniques. Driven by the love for the literati painting, wenrenhua文人画, he deepened the study of the tradition, combining it with painting, poetry, calligraphy and seal cutting.

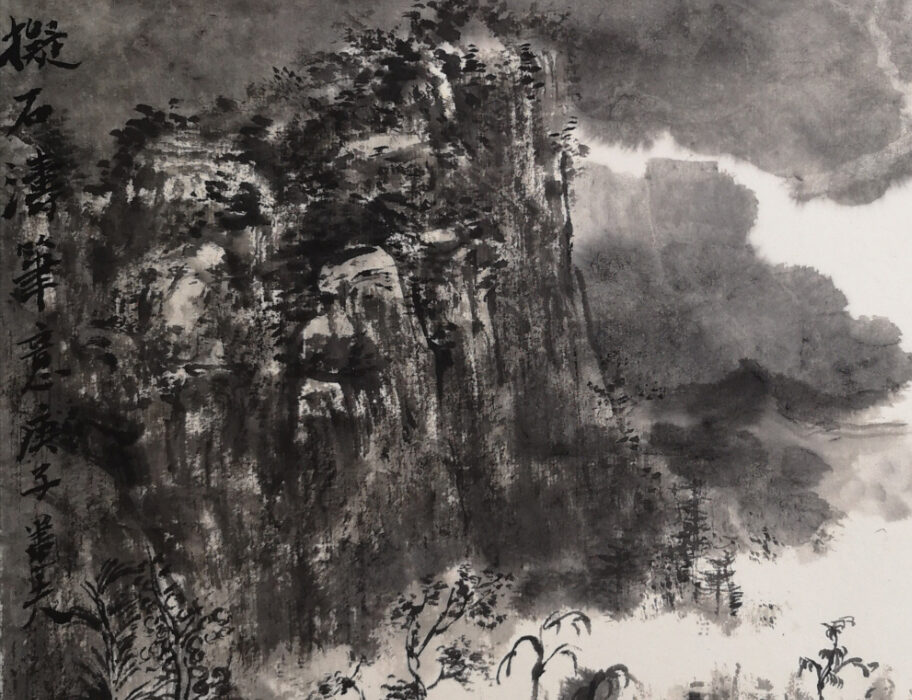

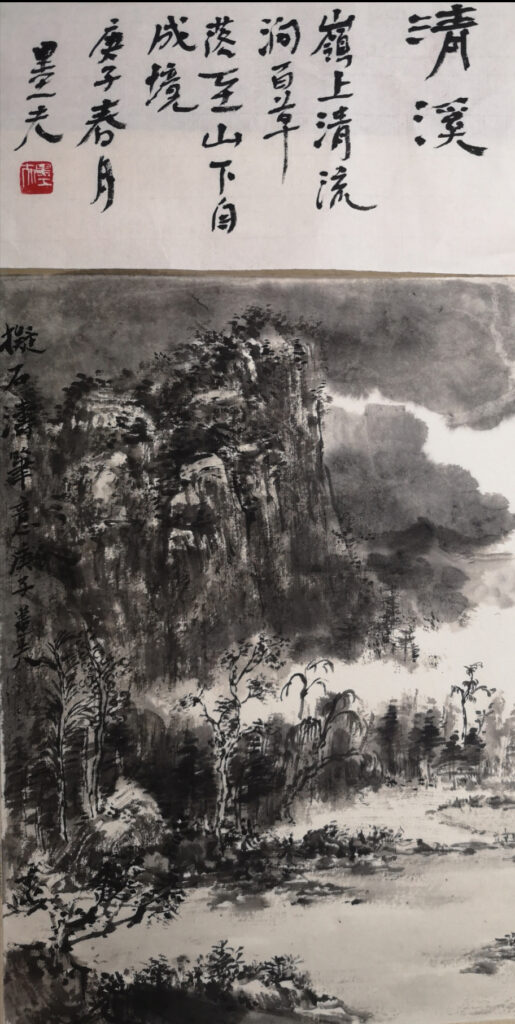

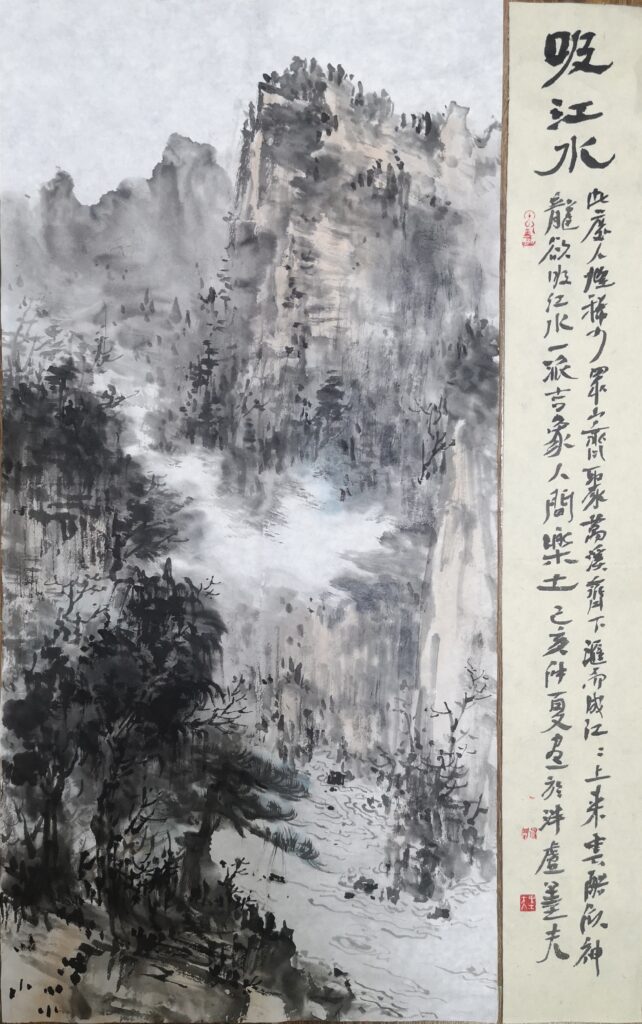

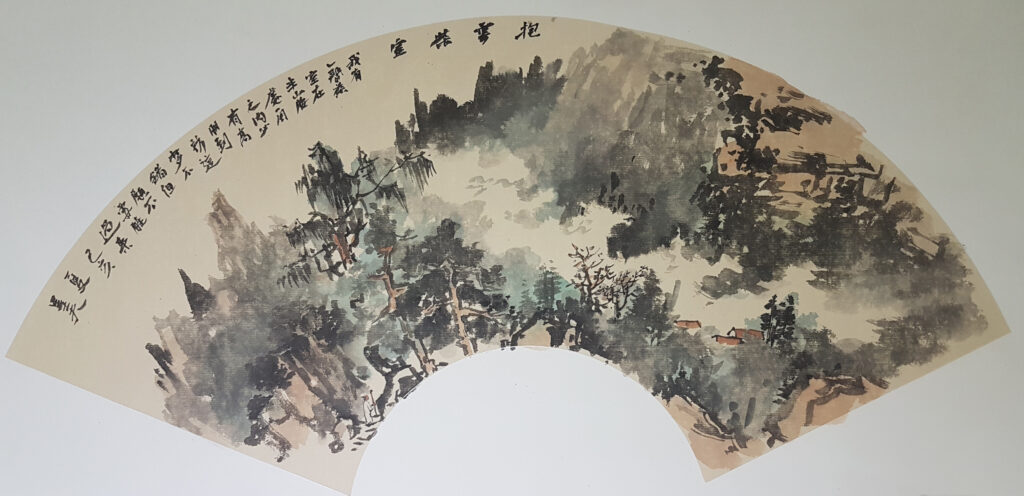

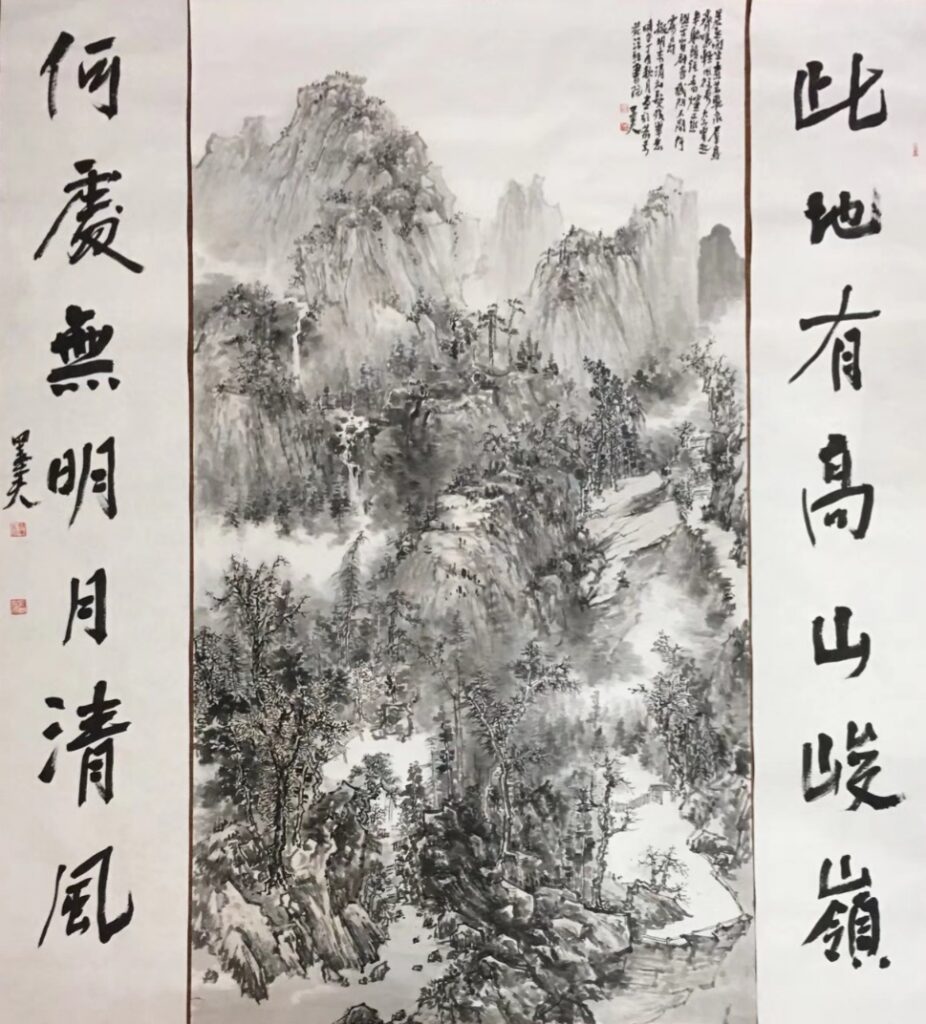

Following the literati vision of art and culture, Cai Liang learned both from ancient and modern masters. Guided by the spirit of innovation and research, he merged the traditions of the wenren hua with free, expressive and powerful uses of the brush. The practice of calligraphy is a fundamental element that blend with the study of painting, for this reason the strokes that characterises his calligraphy and the strength of the carved characters in his seals can be found in his painting. Although he prefers to use smooth and “round strokes” (yuanbi 圆笔), he also uses the “square strokes” (fangbi 方笔), strokes characterized by clear edges and corners, that communicate a sense of determination. The merging of these two brush techniques enrich his paintings creating an inner effect of movement and variation in his works. The free hand brush strokes are able to reflect the verve of the scenery and express the author’s feelings.

The contrast between the ink splashing technique and the use of the lines in Cai Liang’s mountain and water paintings are accompanied by the application of light colours, usually various shades of blue and brown. His accurate and rich use of water reflects the soul of Lingnan school painting techniques, with the result of an ample yet balanced ink and colour changes and shading, that confer a high degree of naturality and vivacity to the depicted subjects.

Mists and fogs are represented by empty spaces, which brings balance and breath to the painting and gives the viewer the freedom of roaming all around the landscape. Sometimes Cai Liang uses a darker background colour in order to represent the sky, and again through the combination of water and ink, the contrast between light and dark sometimes produces a melancholic atmosphere, that adds a romantic charm to his works. The performance of the background, the blank clouds and fog recall echoes of the techniques of the Song Dynasty mountain and water paintings. Mediated by Cai Liang aesthetic taste, artistic views and his powerful brush strokes, he successfully expresses the “image” xiang 象 of the mountains, waters and the other natural subjects of his painting, instead of the “shape” xing 形 in accordance with the theoretical principles in Chinese paintings, against the mimetic representation of the subjects.

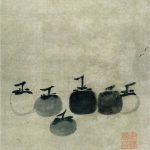

Part of Cai Liang’s artistic productions belong to the category of flower and bird paintings, where he successfully combines the artistic vision of literati, reshaping the traditional themes with innovative spirit. Here the use of the brush and the ink belongs to the category of the Free hand brush style xieyi 写意 (literally means “writing, painting the idea or meaning”). He successfully emphasizes the semblance and the spiritual aspect of the subjects. Like in his mountain and water paintings he doesn’t chase for the physical similarity of the subjects but he is able to grasp its essential spiritual characteristics. Cai Liang’s paintings are both in colours and black and white. The colours he uses are very bright, giving the subject a great vivacity and a strong visual feel, and at the same time expresses the spirit of the subject.

In his black and white paintings, the dialogue between water and ink is extremely rich and precise, making the subject itself express a high degree of vigour that makes the image extremely vivid. Hence, even with the absence of colour in his black and white paintings, our eyes are able to perceive the colours of the subject.

In his paintings we can see the artist’s will to express the spirit of the wenren hua with modern techniques. This type of thinking places Cai Liang within a debate that began in China at the beginning of the last century and which over time becomes more and more varied and animated. The main theme of this great reflection is on in what form painting must express itself in order to express the contemporary spirit of a nation, taking into consideration the current Chinese cultural situation and its relations with the outside world. During the history of Chinese art this reflection has always been present, especially when there were historical changes, such as the establishment or fall of a dynasty. Each historical moment has its own particularities, and the artist’s task is also to express the spirit and character of his era. This reflection often has as its main aspect, the relationship with tradition and how it should be expressed and to which tradition to refer, what are the aspects that best adapt to the state in which the artist operates and how it will draw from it, what to accept and what to refuse, what to change and what to renew. All of this united and synchronized with the artist’s personal style and aesthetic ideas. In contemporary times, this situation arises again in a complexity that is perhaps unprecedented in Chinese history, as China has never had to relate to the world outside it (basically the western one) like now, receiving such a massive influence from all points of view. It is not the first time that China has received influences from cultures that lie within and beyond its borders, what has changed is the amount of these influences and the relationship they have with China and how it relates to them. At the same time, the influence of Western culture, in addition to being on a global scale, also has an aggressive character in some aspects and at the same time China accepts these influences because it believes it is the way to be able to position itself at the same level as Western nations in economic, political, cultural and global dialogue. This had never happened in the past, in fact until the first major defeat of the opium war, which saw imperial troops succumbing to western technology, China had always considered itself the main culture worldwide, therefore the way of relating to other peoples was never on par. The same is true for the artistic sphere, at the beginning of the 20th century China began to come into mass contact with western art, which has a distinctly different approach from that of China, and this influence has brought many innovations , has opened many areas of reflection and continues to open them up to the present. The main problem is how to relate to this great imported system, resulting in very different reactions. There are artists who do not want to come to terms with western art, so they try as much as possible to limit their influences and focus on the study of tradition and how to reinterpret and enrich it without introducing western elements. On the other side of the spectrum of different kinds of attitudes there is one of those who consider it important to embrace western artistic methods, both from a theoretical, ideological and practical point of view, who using the traditional Chinese materials (brush, paper, ink and colors) radically renew pictorial practices, because they see the era of change in contemporary times and find an important source of inspiration in Western art. It should be noted that what defines Chinese painting in general way are the materials used and not so much the techniques, therefore there are no expressive limits if not precisely the material ones, since if other means of artistic production are used, it leads to other practices. In any case, no tradition or artistic vision that is Chinese or Western should be followed slavishly and passively, but it must be learned and reworked, used to enrich one’s vision and artistic practice, in fact the legacy of the masters of the past, or of the contemporary will help to have a vision wider and more complete of the artistic panorama and society in general. Cai Liang places himself in this debate in an intermediate position, which sees the importance of maintaining a close relationship with tradition, in particular that of the wenren hua, but at the same time is aware of the contemporary status of mountain and water painting and western cultural sphere, whose ideas and conceptions often can enriching artistic expression and giving unprecedented impetus to creativity. As already mentioned, the tradition must be inherited, and the artists cannot transform himself into other masters, otherwise his work is just the work of a copyist, without any contributions to the evolution of the arts.

Cai Liang has successfully created his own unique painting style; he came into contact with new conceptions and studied new techniques from the west. Like the perspective of Western paintings, the water colours and oil colours, the lightness in photography, chiaroscuro of the pencil and the dialogue between lights and shadows, and subjects outside the sphere of mountain and water painting, like figure painting and other subjects. His hope is to inject new blood into Chinese painting, which embodies the value of the tradition with a contemporary spirit.

A poem by Cai Liang:

山居

一溪白云抱山腰

林下书童煮茶去

不羡尘世功与名

午后风来拥书眠

Living in the mountains

A stream of white clouds embracing the mountain waist,

The schoolboy under the forest prepare tea.

Don’t envy worldly achievements and fame,

Afternoon wind is here, embrace the books to sleep.

Read the article from the magazine, download it from here