The Art of Wu Shengyuan 吳盛源 – a Painter of the Lingnan School of Painting

Issue 4 – By; Wu Jiayin

The twentieth century has been an era full of possibilities in Chinese painting. The Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts, founded by Liu Haisu, was established in 1912, thus turning the first page in the history of Chinese modern art education.

Due to its strategic role and position within China’s policy of reform and opening up (gaige kaifang 改革开放), there emerged from Guangdong a large number of talents. In terms of artistic creation, one prominent eminent has been the founding of the Lingnan School of Painting 岭南画派, in the 19th century, in Guangdong Province by the Gao brothers (Gao Jianfu 高劍父 and Gao Qifeng 高奇峰) and Chen Shuren 陳樹人, also known as “the three heros of Lingnan” (Lingnan san jie 嶺南三傑). Heralding the revolutionary slogan of “balancing Chinese and foreign [concepts], blending ancient and modern (折衷中外, 融會古今)” in the early Republican era, they confronted traditional art forms that laid emphasis on imitating the ancients. Later, the new generation of Lingnan School artists represented by Guan Shanyue 關山月 and Li Xiongcai 黎雄才 inherited the past and opened a way to the future. They actively engaged in art exploration and strove towards life, their contemporary era, and towards the people. During their years of teaching at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, they cultivated a group of artists with solid painting skills and innovative abilities.

Wu Shengyuan 吳盛源, was born in Chaoshan, in the eastern part of Guangdong Province. Although a remote place, Chaoshan cultivates and perpetuates a tradition of admiring culture and art. In the 1920s and 1930s, the transportation to the provincial capital (Guangzhou) was still inconvenient. Due to the development of the modern shipping industry, it was more practical for the Chaoshan area to contact the outside world by water. The Teochew people would go to Shanghai to conduct business, and cultural exchanges would ensue. Certain businessmen would support youths and thus offer them the opportunity to attend the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts and Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts, and be instructed there by such famous artists as Huang Binhong 黃賓虹 and Liu Haisu 劉海粟. After their graduation, this group of students returned to Chaoshan as art teachers and eventually laid the foundations of the modern Lingdong painting circles. Chen Shilin 陳世霖, Wu Shengyuan’s first teacher, distinguished himself as one of the most accomplished painters in his generation.

Wu Shengyuan ’s first learning stage as an adolescent was conducted by a high-quality teacher, under new circumstances made possible during that period. Later, he was admitted to the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts and became one of the first students to enter the Higher Academy of Fine Arts in the Lingnan area after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Basing himself on the influence of the Shanghai School, he was able to receive solid academic training and inherit the innovative spirit of the Lingnan School of Painting.

His graduation from the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts in 1965 coincided with the ten-year period of turmoils brought about by the Cultural Revolution. As a teacher, he was conscientious and tireless, and trained a large number of students. He then moved to Hong Kong for a few years, before finally returned to his hometown. In the face of the tide of the times, Wu Shengyuan tried his best to avoid external interference and tried everything possible to devote himself to painting. Guided by his sincere love and passion, he watched and drew his hometown all his life.

1 – Poetic pastorale

Wu Shengyuan was born before the founding of the New China and received an old-style education. He belonged to the last generation of people who grew up under the true traditional rural structure. This caused him to harbour the “nostalgic” feelings of the traditional literati. He thus grew up in a relatively relaxed environment, benefiting from the understanding and support of his well-informed grandmother. The cost of painting materials was not low for a farming family, but his grandparents were still willing to support him. Thanks to his family’s encouragement, he was thus allowed to practice art in his free time. Roaming through the countryside, he would also and inadvertently accumulate a large amount of material that would prove precious for future artistic creations.

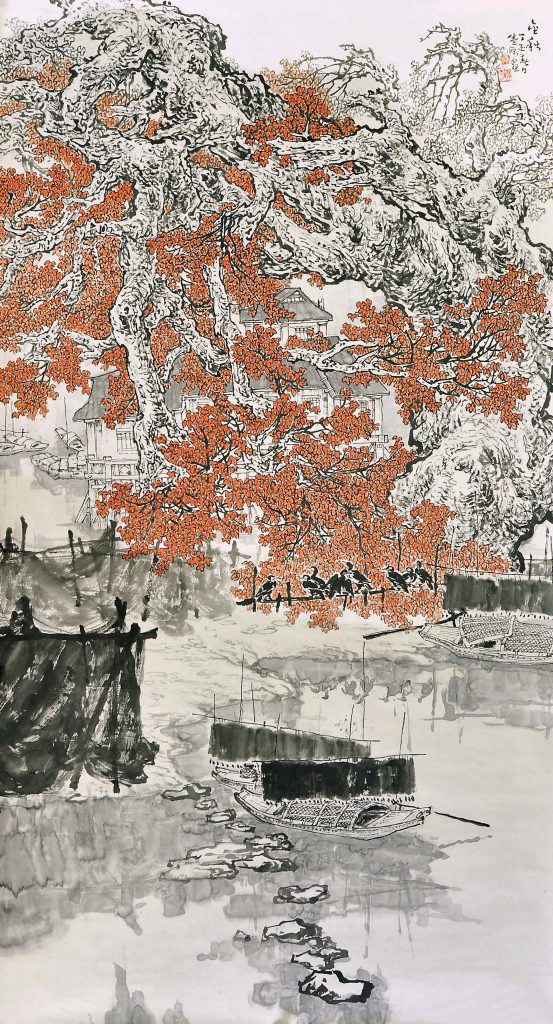

The deep attachment to his homeland is rooted in Wu Shengyuan’s heart. In 1989, who had by then moved to Hong Kong, he returned to his hometown of Luxi 胪溪, a remote village. After his return, he created many important works such as Golden Autumn, Jin Qiu 《金秋》(140×70, 1993, fig.1), The Homeland Scenery Ever Haunts In My Dreams, Guyuan Fengwu Mengchang Ying《故园风物梦常萦》(140×70, 1994, fig.2), Morning Mist, Chenwu 《晨雾》(70×140, 1994, fig.3), etc. In these artworks, one may see what Sun Ke 孫克 has defined as “a quiet and deep flavour” obtained through the “blending of magnificent scenes and unique styles”. Wu Shengyuan’s later paintings gradually entered the realm of pure artistic mastery. Compared with his earlier period of freshness, later creations are more magnificent, rich, and profound.

It is this strong emotional bond between Wu Shengyuan and the homeland that we find in the paintings, i.e., not only the painted surface depicting the pastoral scenery, but also the warm, strong and profound pastoral feelings. Reading his paintings, often takes the mind to Su Shi 苏轼 ’s poems.

Bucolic scenes, rural households, trivial matters of everyday life, and things that most people may ignore — all are turned into poetic scenes in Wu Shengyuan’s paintings. His aesthetic appeal and humanistic vision lie at the core of his art. In his eyes, labourers are beautiful, as are the mountains and rivers in his native countryside. Contrarily to the people who only glance at the scenery, Wu Shengyuan has been living in the countryside for many years. Therefore, his works are endowed with a calm and lush atmosphere, the warmth of the village and the warmth of the world, and the quiet and peaceful flavour of oriental poetry.

Wu Shengyuan’s paintings are both lively and playful and playable. On the one hand, this comes from his deep familiarity with the countryside, his strong sense of observation, and his profound life experience. Even such minute details as houses vary from one painting to the next. Many scenes do not rely on past experience but are directly extracted from life. On the other hand, this is also due to the vividness of the characters depicted in each work. For decades, he has been very attentive to characters. In his works, we may see the farmer in the spring, the flute player seated on the back of the cow in the summer, an autumn conversation, and the idle sitting in winter. As Wu Shengyuan’s painting developed to reach its late, mature stage, the small figures animating his landscapes become fuzzy and stylised. The peaceful and quiet natural order in the painting brings a long-lost sense of peace and security which pervades the spectator and allows his heart to calm down, while he loses himself in contemplation.

It is precisely because of the painter’s sincere passion and superb skills that every painting has a different feeling. The vibrant and concrete things that come from nature constitute breakthroughs in the stylisation of traditional landscape painting. Wu Shengyuan pioneered a path and created a large number of idyllic paintings of his own. These may appear as easily attainable, but does in fact require highly attuned compositional skills.

2 – The landscape in the heart

As a landscapist, Wu Shengyuan spent most of his time painting outdoor scenes. Having received solid academic training, he devoted himself to copying and studying ancient paintings for many years even after his graduation. Guided by the innovative spirit of the Lingnan School of Painting, his painting language is very rich, both traditional and modern.

On the other hand, he traveled extensively, drawing and painting en-plein air. Faithful to the artistic purpose of “learning from nature”, shi zaohua 师造化, he traveled all over the country and created a series of magnificent works that express the mountains and rivers of his motherland.

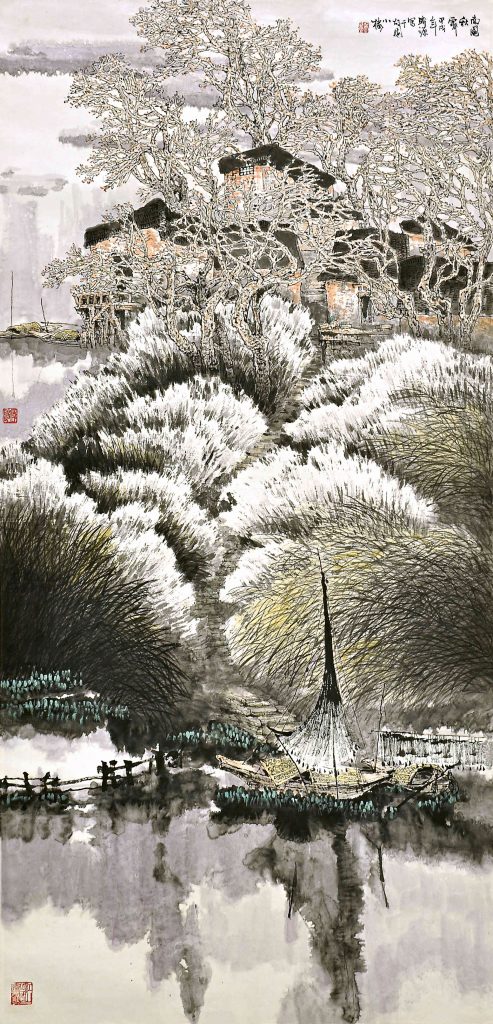

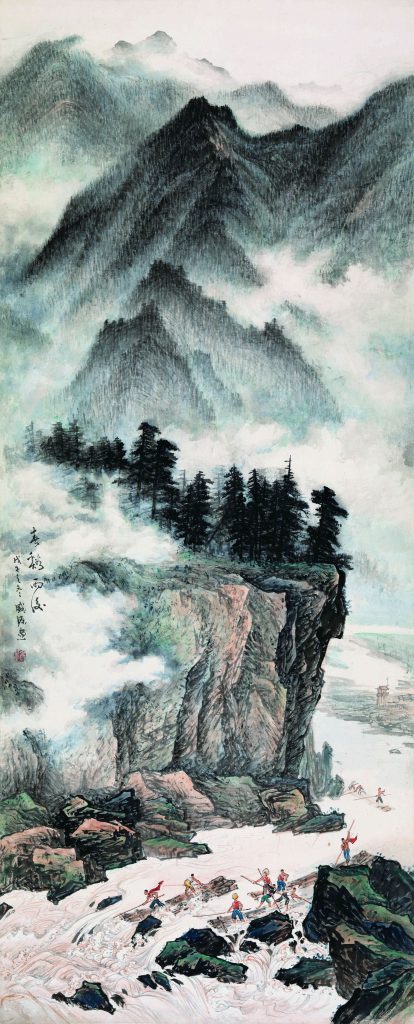

In his landscapes, one may find the dense layout of Wang Meng 王蒙, the gentleness of Tang Yin 唐寅 ‘s brush-and-ink, and the rigorous structure and vivid momentum of Li Xiongcai 黎雄才 ‘s stone pine trees. He not only avails himself of traditional materials, but also creatively uses ink textures. The new atmosphere and techniques have allowed him to transcend tradition. He often uses meticulous language, but can also create magnificent momentum. Spring Brook After the Rain, Chun Xi Yu Hou 《春溪雨后》(fig.4), created in 1964, was selected for the 4th National Art Exhibition. In this painting, the distant view is densely brushed, and the texture of the rocks is neatly described. The scenery in the painting’s central area is precipitous and steep, and the labouring figures in the foreground are dynamic and beautiful, while the momentum of competition among many ships is almost palpable. Clouds and water linger and act as the picture’s stabilising element. Tension, but also harmony and unity, may be felt throughout the whole work, which perfectly realises the transition between plein-air sketching and creation. Throughout the 1960s, the landscape painters actively participated in social life within the new social context. The techniques and content of traditional landscape painting were thus greatly expanded. It is obvious that traditional landscape painting was a result of its encounter with a new historical context.

Wu Shengyuan emphasised the beauty of brush-and-ink, and the rhythm of his brush strokes, which was blunt and powerful. This was inseparable from his long-term emphasis on calligraphy. Apart from the large-scale landscapes, his brushstrokes can also be found in his landscape sketches. Peaks, mountains, rocks, trees, clouds, and water — the line texture is thick and spiritual. These are works crafted with ingenuity, combined with smooth ink, uncommon momentum, and vivid charm.

3 – Ingeniously inspired

“Learn from nature on the outside while finding the source in your heart”wai shi zaohua, zhong de xinyuan 外师造化,中得心源. Wu Shengyuan observes the external natural objects quietly, and possesses strong image memory and styling ability. The external objects are not limited to mountains, rivers and seas, but may also be as subtle as rain marks on an old wall, or the reflection of a tree, or an old photograph. At the same time, he is also good at using poetry and recombining these materials. Eclectic, accommodating and innovative — scenes that may appear ordinary in the eyes of others have a strange brilliance in his vision.

Wu Shengyuan pays great attention to the effect of ink, and he has focused on the study of ink textures and effects for a long time. He also knows that colour does not hinder ink, and ink does not hinder colour, thus bringing them to enhance each other mutually. Day after day, year after year of exploration, he has become proficient with the brush and has a rich and varied vocabulary of brush-and-ink.

Both People in the Moonlight, Yuese Renjia 《月色人家》(fig.5), created in 1991, and Morning Mist, Chenwu

《晨雾》have a sense of fantasy and loneliness. In People in the Moonlight, the old branches under the moonlit night appear like dragons, constructing a complicated and mysterious world. Morning Mist is a scene of dawn presenting a childhood realm. The winding old trees, the hazy morning mist, and the rich texture of ink create a dreamlike feeling in the morning.

Wu Shengyuan has a simple personality, is gracious to others, is easy to get along with, and has always maintained his peasant qualities. His life coincides with a historical period of consequent rapid changes and developments of Chinese society. Unheedful of the outside world, he has been like a day for decades, being an honest man, painting seriously, and experiencing the joy of painting in quiet solitude. This persistent spirit is truly admirable!

Read the full magazine